By Michael Jansen

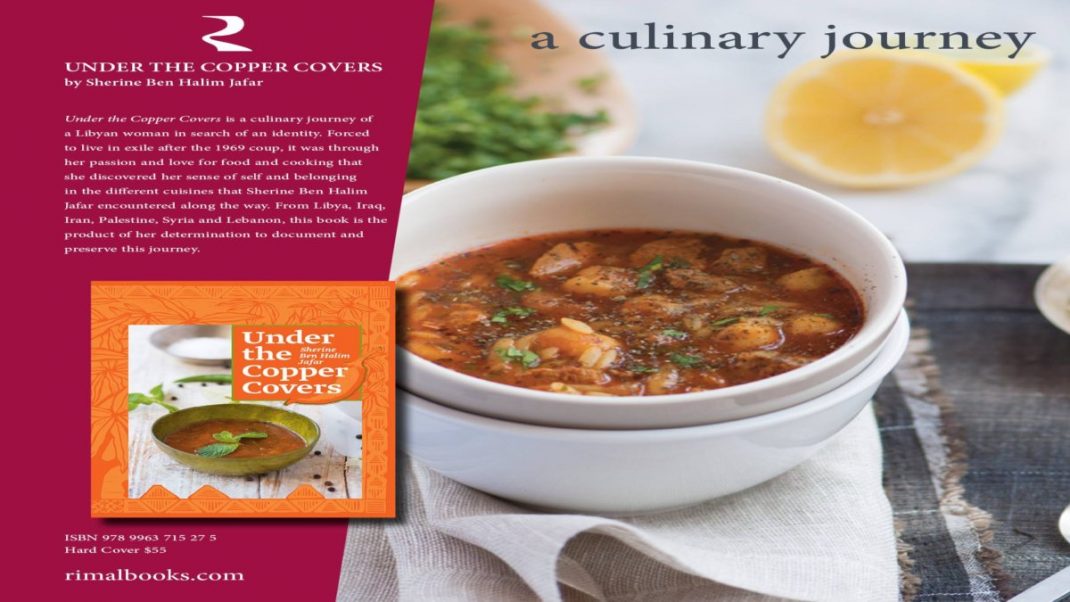

Under the Copper Covers is both a cookbook with a story and a story of a cookbook. Published by Rimal Press and on display at its stand at the Sharjah International Book Fair.

The book contains recipes from half a dozen countries for dishes that sustained author Sherine Ben Halim Jafar during her troubled nomadic existence and provided her with an outlet for expression once settled in Dubai.

Jafar is the youngest child of former Libyan Prime Minister Mustafa Ben Halim and his Palestinian refugee wife Yusra Kanaan, an adventurous cook who exposed her brood to Libyan and Palestinian culture and food from an early age.

Ben Halim fled Tripoli in 1969 following the coup mounted by Muammar Gaddafi against King Idris, taking his family on a journey in search for security and permanence.

The family briefly settled in London but moved to Beirut where Ben Halim, an engineer, set up a contracting business connected to leading construction firms. Denied documents by the new Libyan regime, he obtained Saudi passports and eventually Saudi nationality for himself and his family.

In Lebanon, Jafar made a host of friends of different nationalities at school and savoured Lebanese and Syrian food. Syrian dishes were special because her maternal grandmother was Syrian. But when kidnappers commissioned by Gaddafi attempted to kidnap her father in 1973, he took his family back to London, to British intelligence protection against abduction and assassination. Jafar, then nine years old, took the move badly, becoming panic stricken, plagued by uncertainty, yearning for Beirut and hating a series of London flats.

She writes, “The only place where I was to find solace was within the walls of the kitchen, with the comfort of my mother’s cooking and familiar smells. It did not matter what ingredients she was using, which cuisine, culture or style — comfort was Mum and her food. My sense of belonging was measured by her cooking. Whatever Mum cooked was who we were, what we were and where we belonged.” Her Libyan aunts reinforced these feelings.

Enrolled in a new international school, Jafar was depressed and suffered panic attacks, exacerbated by repeated moves. At each flat she would shelter in the kitchen where she baked her first cake at 11. Baking became the therapy that lifted her from despond and depression.

With the 1979 Iranian revolution, a wave of Iranian exiles arrived in London. Jafar’s two new best friends introduced her to rich and varied Iranian rice dishes. She learned the basics of preparing them while staging events featuring the foods and national dress of fellow students.

When Jafar was 12, the Ben Halims moved again to a flat where her mother made Saudi friends and experimented with Palestinian dishes while her father became an advisor to Saudi King Fahd. Her father was again threatened by Gaddafi and had to be attended by relays of British special branch men while a third was on duty at the flat. The men sat in the kitchen and enjoyed delicious meals prepared by the Ben Halim’s Egyptian cook while threats from Libya swirled outside the Ben Halim home.

When her school offered to raise funds for Save the Children, Jafar and her friends held a bake sale including a range of Middle Eastern delicacies and followed up by staging an international evening of food. Lebanese, Iraqis, Greeks and Egyptians disputed over dishes they would make. Jafar cooked a spicey meat and rice Saudi dish and donned Saudi dress, a Libyan-Palestinian representing the kingdom. At university Jafar’s study of literature showed her that others also suffered from a sense of insecurity and searched for identity and meaning in this turbulent world.

With the aim of “discovering the place where [she] belonged” she decided to marry a “suitable Arab” to free herself from the physical and emotional constraints of home. Although this was a traditional path for a rather untraditional young woman, she chose another exile, son of an Iraqi father and Lebanese mother, Imad Jafar, rather than an Arab groom settled in his own country. She initially had problems, however, as Saudis had to have government permission to marry non-Saudis and her decision to marry an Iraqi coincided with the war to drive Iraq from Kuwait.

The family joked, it was a marriage of “diplomatic inconvenience.” After a Libyan-Iraqi wedding, the couple moved to Washington, DC, where she began to confront complicated Iraqi dishes. But the US did not feel like home to this wandering Arab pair who, after a visit to Dubai and Sharjah, decided to settle in Dubai where Imad Jafar, a dentist, settled into a new medical practice.

Sherine, after a number of painful miscarriages, gave birth to two Libyian-Palestinian-Iraqi-Lebanese girls and resumed her quest for perfect plates in the six different cuisines she had learned to cook in her troubled journey from Tripoli to Dubai.

During the Libyan revolt against Gaddafi, Jafar was proud to proclaim herself a Libyan once again and following his fall Jafar paid a brief visit with her family to Tripoli.

There they visited their house before returning to Dubai where she compiled her cookbook, consulting experts in each of the six cuisines she put under copper cover.

Sherine Ben Halim Jafar’s journey is not unique although her father’s pre-Gaddafi political role complicated her young life.

She is one of tens of thousands of displaced persons, many of mixed descent, from this region over many generations — Palestinians, Libyans, Syrians, Iraqis, Iranians, and Lebanese — who have had to discover their identities and find their paths in life in exile, often far from this beloved sunny, charming, and culturally rich but deadly and devastated region.

For exiles food from “home” is portable, stored in memory or gleaned from books found in exile rather than packed in a suitcase; food for the soul: it refreshes identity, gives solace, and uplifts.

***

My dear friend Suad al-Radi, an Iraqi great lady, lived most of her life in exile in Lebanon cooking Iraqi food for family and friends. When she paid her annual visit to Baghdad she would return to Beirut with a cold box of Kibbeh Muslawi, rounds of bread filled with cheese, meat and herbs, and date delicacies, a taste of “home.” Her expatriate daughters Selma and Nuha used to indulge in a soul feast when Suad trundled her bounty through the door of their flat.

In this book, Jafar has offered readers the opportunity to feast on soul food.

______________

The Gulf Today