By Marta Bellingreri

A group of local activists from the Amazigh-majority city of Zuwara in Libya are taking matters into their own hands and working to prevent illegal immigration from the shores of North Africa toward Europe.

“If we want to rebuild the Libyan state, we need to start with protecting human dignity,” said Badis Halab, a 23-year-old member of the At-Wellol Movement (People of Zuwara) in Zuwara, an Amazigh majority port city in northwestern Libya. “So even when we have to struggle for our own life in the Libyan chaos, we cannot ignore refugees and migrants who continue to die at sea in front of our shores,” added Badis.

At-Wellol and Azref , another civil society movement, are made up of around 30 members, both men and women aged between 20 and 30 years old. The organizations have played a major role in pushing the Zuwara municipality to arrest people who smuggle migrants, an initiative that prevents illegal departures from the 75-kilometer (47-mil) coast of Zuwara in northwest of Libya. The municipality’s official estimates of inhabitants in the Libyan Amazigh city stand at 60,000 people in the area between Ras Jdir on the Tunisian-Libyan border and the city of Sabratah, the first city east of Zuwara. Amazigh, which means “free humans” or “free men,” also known as Berbers, are the indigenous people of North Africa and comprise 5% of the Libyan population.

The first protest that Azref and At-Wellol organized against smuggling was in 2014, but this did not lead to any major change. In late August 2015, dozens of corpses of migrants washed ashore on the Zuwara coasts, and the activists reacted immediately by organizing a bigger and more visual protest. On the main road of the Zuwara city center, the two organizations displayed pictures of the corpses in order to speak directly to the people and raise awareness of the deaths at sea. But the demonstrators also had a direct demand aimed at the local municipality: Arrest the smugglers to prevent illegal migration and the consequent mass death.

As a result of their activism, the municipality involved the so-called “Masked Men” militia in seizure and arrest operations led by the police. Some of the arrested smugglers were sent to Tripoli’s jails; others are held at the small Zuwara prison.

The municipality continues to monitor illegal departures and arrest smugglers, but thousands of people continue to leave for Europe from nearby Sabratah, Zawiyah and Tripoli, with corpses ending up on Zuwara’s shores. The cities’ own coast guard and coast guard and fishermen are involved in some of the rescue operations.

There are many reasons why people are fleeing Libya, such as continued fighting against people associated with the former regime of Gadhafi — and the current instability in Libya, where the Amazigh are victims of discrimination and violence. During Gadhafi’s rule, the Amazigh were expressly forbidden from practicing their historical customs, celebrating cultural holidays or giving their children non-Arabic names.

Zuwara had been, especially in the last years of Gadhafi’s rule, the main departure point for illegal migrants. Refugees from the Horn of Africa and from West Africa were detained during Gadhafi’s time in detention centers at the desert’s doors under horrible conditions. Detention centers for migrants and refugees in the country continue to be sites of extreme violence, an issue reported by refugees themselves who bear the signs of torture. The United Nations and other human rights organizations worldwide have reported such practices in detention centers. Following this widespread reporting on their area, civil society local activists said in conversations with Al-Monitor: “We want to change the reputation of Zuwara from being a smugglers’ city into a legal and safe city for all.”

Another important issue is law enforcement. The two local organizations believe that in order to rebuild a state, law enforcement and fighting corruption must be among the driving forces. Given that Gadhafi’s rule was based on a system of personal ties and nepotism, the mechanisms of law were subjected to the eccentric leader’s decisions and interests.

In his recent autobiographical novel “The Return,” exiled Libyan writer Hisham Matar considers the conflicts that erupted after the 2011 revolution as a result of 40 years of oppression under Gadhafi’s regime and ideology. According to the novelist, Gadhafi’s contradictory and mystifying ways of interpreting democracy ultimately led him to create laws for an autocratic monitoring of the people and to enact brutal suppression of dissidents.

Thus, revitalizing the area does not only rely on directly confronting the problem of migrant smuggling, but also on rebuilding an entire culture that was suppressed for a long time. The two Amazigh civil society organizations are seeking to transform the previous system by involving young people in their cultural activities. This will help prevent young people from resorting to illegal smuggling activities as they reel under poor economic conditions.

“Azul” is the Amazigh word for “hello,” and for the people of Zuwara, it represents a welcoming greeting. The Libyan Amazigh population of this coastal city is revitalizing its written and spoken language, which was forbidden during Gadhafi’s reign. There are a large number of language-based initiatives organized by groups attempting to help the city in different social and cultural aspects.

While the At-Wellol Movement organizes an annual festival of cultural diversity and works on theatrical projects that tackle gender issues, Azref has focused more on the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

“We are doing what the government should normally do but cannot do under these exceptional circumstances,” said Anir, an activist with Azref. Azref has also tried to create a special passport for migrants staying in Zuwara in order to give them a certain legal status, but the news spread to other cities where illegal migrants live and the organization has had to repeal its decision in order to avoid the spread of fake papers across Libya.

The path to stability remains extremely long, and all these young activists continue to suffer from the psychological effects of the revolution and the civil war that ensued in 2014: “We witnessed death and wounds of friends, and then corpses of migrants on the beaches,” said Mohannad Dhan, a 27-year-old member of At-Wellol. “Despite it all, At-Wellol and Azref in Zuwara want to send a message of peace to the world.”

***

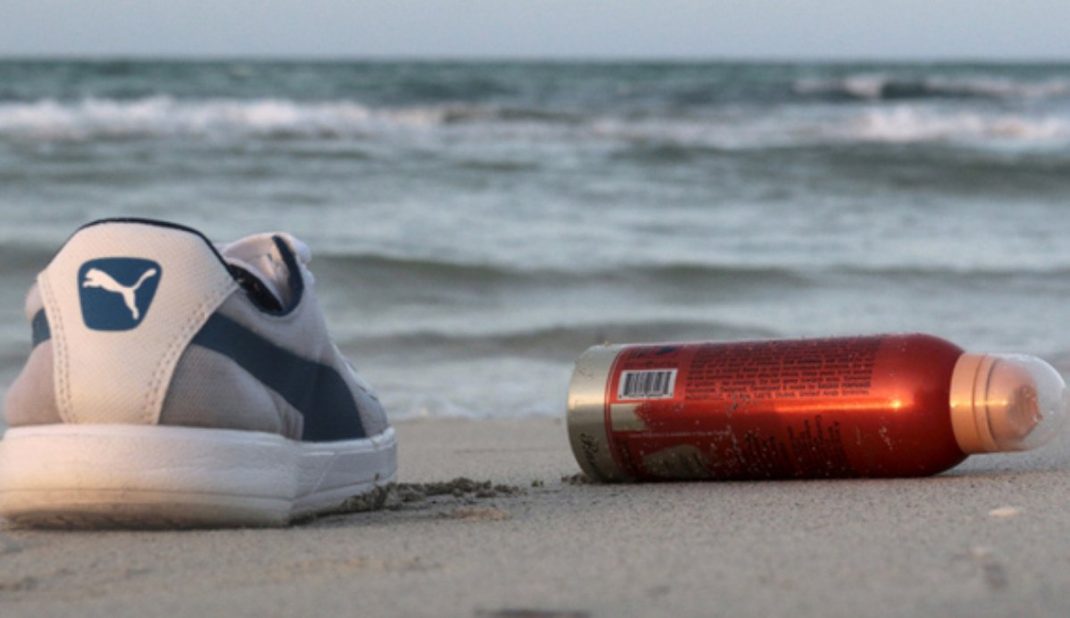

Image: The belongings of migrants, recovered by the Libyan coast guard, are seen after the migrants’ boat sank off the coastal town of Zuwara, west of Tripoli, Aug. 27, 2015. (photo by REUTERS/Hani Amara)

***

Marta Bellingreri – An Italian writer, Arabist and cultural mediator. She has lived and worked in many MENA countries, particularly Tunisia and Jordan.

___________