By Lamine Ghanmi

Ibadiyya is an early denomination of Islam whose followers hold several views contrary to the Sunni and Shia sects.

^^^

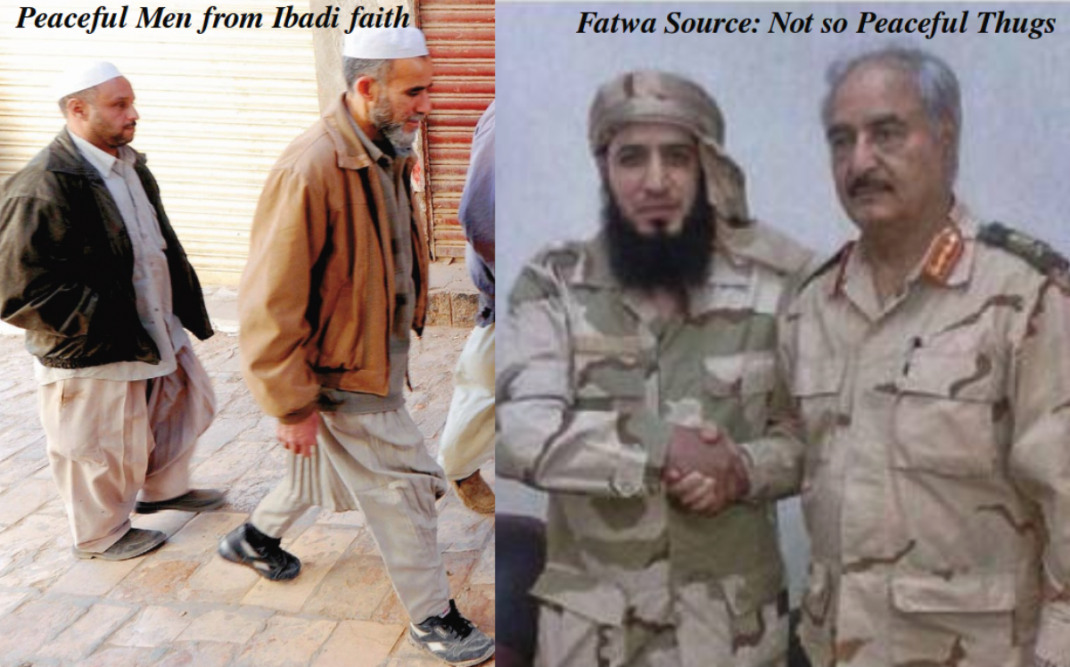

A fatwa in Libya labelling members of the minority Ibadi sect as “infidels without dignity” raised concerns that sectarian violence could break out in neighbouring Tunisia and Algeria, where many of the group’s followers live.

Libya’s Supreme Fatwa Committee, the religious arm of the Bayda-based government in the east, ruled that “Ibadiyya is a misguided and aberrant group” and that “its followers are Kharijites with secret beliefs and infidels without dignity.”

Ibadiyya is an early denomination of Islam whose followers hold several views contrary to the Sunni and Shia sects. Ibadi Muslims have been accused of links to the Kharijites, Muslim dissidents who opposed the authority of the caliphate in the early years of Islam.

The fatwa, issued in response to public concern over whether it was suitable for Muslims to be led in prayer by an Ibadi preacher, was criticised by Libyan intellectuals and rights activists, who expressed concern that the statement could unleash religious discord in a country reeling from years of tribal, regional and political division.

It also builds on a long history of religious oppression and exclusion in Libya. Since the overthrow of Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi in October 2011, extremist Islamists have attacked members of religious minorities and their religious sites. In February 2015, the Islamic State (ISIS) took responsibility for killing 21 Egyptian Copts in Sirte. The group also destroyed Sufi shrines and landmarks in Misrata, Tripoli and Zliten.

The committee behind the fatwa is part of the religious authority of Libya’s eastern government, which is one of three bodies vying for control of Libya.

Ibadiyya, which predates the major Sunni and Shia branches of Islam, has long been viewed as a third way. Its followers are relatively few and live predominately in Oman, as well as in eastern Africa’s Zanzibar Island and various regions in the Maghreb.

In the Maghreb, the Ibadis’ presence has for centuries been characterised by peace, tolerance and prosperity.

In Libya, most Ibadis live in the mountainous Nafusa region and in Zawiya. In Tunisia, the Ibadis’ presence on the island of Djerba has been credited with preserving a peaceful coexistence with the area’s Jewish population.

Approximately 500,000 Ibadis live in Algeria’s M’zab Valley, near the southern town of Ghardaia. The valley was one of the few areas spared during Algeria’s devastating civil war in the 1990s.

However, in March 2014, violence broke out between Ibadis and Sunnis after a Salafist preacher read an anti-Ibadi fatwa on television. Dozens of people were killed before the Algerian Army ended the strife.

In Libya, where key institutions such as a national army, law enforcement and judiciary, are dysfunctional or hobbled by rival militias and political factions, the fallout of sectarian violence could be worse.

“Salafist takfir of the Ibadiyya and incitement against its followers could force the latter to resort to the takfir as well and this will plunge our society into a vicious cycle of takfir and fanaticism,” said Libyan writer Omar al-Koukli.

“Fanaticism is the threshold of extremism and terrorism. That is why such takfir fatwas must be banned by law [because] they incite killing.”

Watchdog group Human Rights Watch urged Libya’s interim government to “stop pandering to extremists by castigating minorities in incendiary language.”

The government, however, defended the committee as a body committed to upholding values of “moderate Islam.” It did not specifically address the edict against Ibadiyya that caused an uproar from Libyan activists, academics and politicians, who warned in a joint statement against the “risk of inflaming sectarian violence” and compared the committee to a “terrorist group.”

“We perceive the genuine victory against terrorism comes by opposing all kinds of hatred and violence and strengthening the foundations of dialogue, pluralism, democracy, civic activism and by pursuing the path of the democratic process that terrorists are fighting with weapons,” the statement stated.

Extremist Salafists have become an increasingly strong social influence in eastern Libya following the Libyan National Army’s fight against the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamist jihadists.

The committee caused concerned after it urged authorities to enforce the draft fundamental law, which specifies that Islam is the source of legislation, and ignore calls by activists that the text enshrines respect of freedoms, including freedom of conscience. “The committee controlled by the Salafists wants a [ISIS-styled] state in Libya, a state that turns its back to the future and plunges into the past,” said Libyan writer Omar al-Kukali.

“A constitution that does not include ‘freedom of conscience’ is a legalisation of intellectual terrorism,” said Libyan rights activist Salem al- Oukali.

The Salafists’ alliance with Libyan Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s forces emboldened Salafists in eastern Libya to claim more power and demand more of a say in social life. They pushed for limitations on women’s rights and freedom of expression and criticised intellectuals and civil society activists.

***

Lamine Ghanmi is a veteran Reuters journalist. He has covered North Africa for decades and is based in Tunis.

_______________