By Mary Fitzgerald and Tarek Megerisi

The question of housing, land and property rights is so difficult—and so important—because it touches on the fundamental question facing post-2011 Libya: what do Libyans want the new Libya to look like?

This paper will examine both the history and the current impact of Qaddafi’s redistribution laws. In addition, we will ask what we can learn from the failed efforts to resolve these property conflicts since 2011.

PROPERTY, POLITICS AND IDEOLOGY

Property reform was in many ways the raison d’être of Qaddafi’s revolution. He exploited the inequality between those close to the former king in eastern Libya (who had secured the large Italian colonial estates on independence), capitalists in Tripoli and the population at large.

His ideology can be explained as an attempt to gain popular support by empowering the disenfranchised within a tightly regulated environment. As he put it in a speech in 1973, “it must be clear that the Jamahiriya [or ‘state of the masses’ system] represents the people’s power and that no opposition can exist outside the system in which, naturally, every individual has the right to express himself and defend his opinion”. 14

Moreover, a system such as the Jamahiriya relied on a high level of public participation, a demand that could be met only by younger, unencumbered elements of the population. Everything rested on the regime’s ability to mobilise politicised youth.

Qaddafi hailed from a small town and a historically unimportant tribe, the Qaddadfa, which meant that his political ambitions depended on supplanting the wider tribal hierarchy and influential families in large cities.

By offering property and other benefits, he was able to mobilise supporters and dismantle opposition. But, over time, the lack of employment, opportunity, and development in Libya meant that his political power became increasingly tied to his patronage rather than the ideology he initially espoused. Likewise, the injustices created by Law Number 4 and other ‘equalising’ reforms created disenfranchised groups whose resentment led to worsening unrest.

Qaddafi’s policy of constant upheaval, reflected in his disdain for institutions and his attempts to dismantle them, made it impossible for Libya to develop a codified, structured system of law. Instead, power rested with temporary bodies such as the revolutionary committees, whose members he enriched.

Yet even these were weakened by internal divisions. Up to a point, this weakness was deliberate, Qaddafi wanted to prevent any challenge to his cult of personality. Constitutional and legal chaos enabled him to ignore red tape. Office-holders were loyal to him and if they weren’t, their committees could be abolished by a new set of adhoc measures. The result was a culture of deadlock and corruption that exacerbated regional rivalries.

THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT

In his quest for complete control of Libya, Qaddafi sought to erase the strong tribal and regional identities of the country. He did not try to abolish the tribes, but instead used their land claims to divide them and create bastions of loyalty to himself.

For example, he granted one community, the Tawergha, rights to prime agricultural land. The Tawergha traced their ancestry to slaves brought to the Libya before the Italian colonisation. Having traditionally lived in Misrata’s coastal hinterland, they found favour with Qaddafi who helped develop their town, which is called Tawergha.

He also installed many Tawergha in the public sector and security forces. This reawakened historical tensions between the Tawergha and other communities in the region, some of which was rooted in racial animus towards the predominantly black minority.

As Libya went through rapid urbanisation and nomads abandoned their pastoral lifestyles, Qaddafi made sure that the new tribal landscape would be favourable to his ambitions.

In 1972, for example, the Mishashiya tribe, who had historically occupied lands that ranged from the Western mountains to the south, depending on the season, were relocated en masse to land in the Al-Awiniya region of the Western mountains—land which was also claimed by other communities.

The tribe received infrastructural investment while neighbouring communities lost political influence and saw their towns slide into dilapidation. Other tribes in the region, including the Zintanis, were given far fewer favours and were resentful.

As tribal unrest grew, the regime passed a ‘Code of Honour’ in 1997 that held families, towns or municipalities responsible for any anti-regime agitators among them. This code enabled the regime to inflict collective punishment and deny communities government services.

In Tripoli, Qaddafi gave favoured tribes and families homes in desirable areas of the city. The social cost of this policy was high: living in an unstable environment where personal wealth and accomplishment could disappear overnight, many Libyans withdrew into traditional support structures of community and tribe.

Law Number 4, the appropriation of private businesses by ‘people’s committees’ and the eradication of private savings meant that merchants, business owners, professionals and landed families all lost power. Not surprisingly, this sparked an exodus of Libyans who had the means to re-locate themselves.

Libya lost expertise in many fields and acquired a strong opposition in exile. Qaddafi was able to mitigate the economic impact of these policies by using Libya’s oil revenue (he quickly renegotiated the country’s oil concessions), which had the added political benefit of making people economically dependent on the regime.

Eventually it became impossible for anyone to operate outside the public sector. The ‘revolutionary initiatives’ advanced in Qaddafi’s 1977 Sebha declaration clearly linked the regime’s economic and political goals by abolishing the “administrative, regulatory and legal institutions that were needed to establish markets internally”. 15

Libya was left with an industrial sector that served no foreign markets and simply saturated the domestic one. The agricultural sector also wilted without any strategic investment. Instead, $27 billion was spent on the Great Manmade River project intended to irrigate the entire north.

The crash in oil prices and the sanctions levied as punishment for the Lockerbie bombing combined to reduce Libya’s revenues from $21 billion in 1985 to just over $6 billion in 1986. 16

Qaddafi had to resort to international borrowing for the first time and lost the liquidity he needed for his large-scale patronage.

The housing drive stopped in its tracks as a result of the cutbacks. All this demonstrated how little was left of Libya’s market economy and how dependent Qaddafi was on external capital inflows. It also highlighted the short-sightedness of his patronage system, as the public sector grew increasingly unable to support the weight of the salaries it was feeding.

SAIF AL-QADDAFI AND THE LIBYAN ‘INFITAH’

In the late 1990s, Qaddafi attempted to buy off many groups aggrieved by his regime, including the victims of the Lockerbie bombing and Abu-Slim prison massacre. As part of this policy, Qaddafi’s son, Saif al-Qaddafi, also launched an amnesty.

This allowed Libyans living abroad to return to the country and to receive financial compensation for the confiscation of their land and property. But this was done without any “formal apology, disclosure of information that could shed light on the events, or concession of responsibility”. 17

This amnesty coincided with another residential housing drive. By the early 2000s, home owners were once again permitted to rent out their property, although only on an informal basis. But because Law Number 4 remained on the books, many Libyans were wary about renting property to other Libyans, as tenants were still legally allowed to claim ownership of their rented homes in the event of any dispute with their landlords.

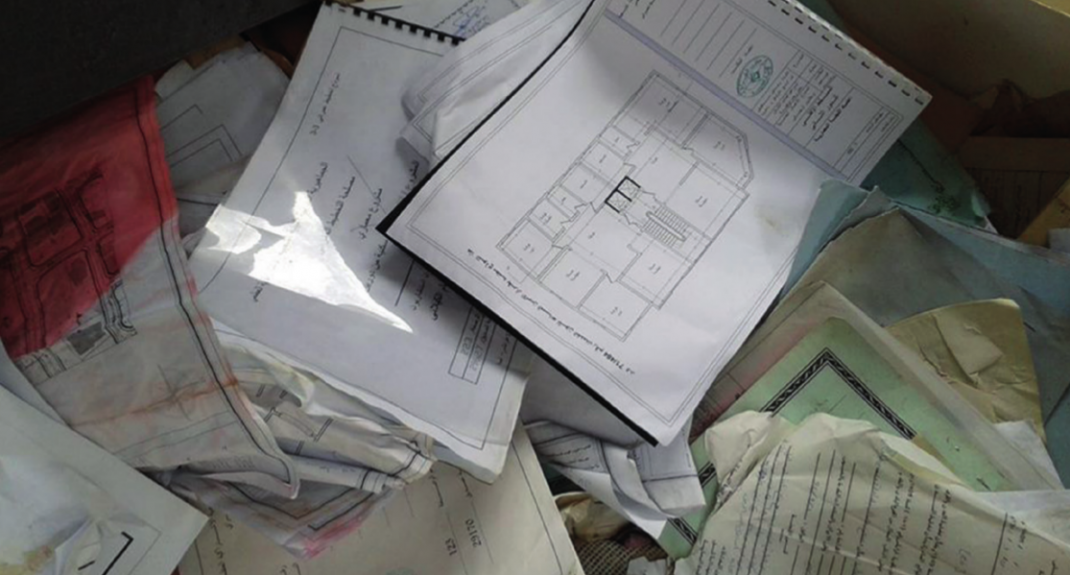

In 2006, Saif al- Qaddafi turned the amnesty into a more thorough attempt to address widespread discontent with his father’s distributive reforms. In 2006, Libya created a High Committee for the Compensation of Properties, along with district offices in various population centres.

A token monetary compensation or the promise of a new flat was offered to those who had lost their property. However the committee itself was perceived as corrupt and moved slowly. Its presiding judge, Yusuf Hnesh, argues that “in the relatively few cases where people were offered compensation, it was a fraction of the current value, and most people refused to take it.” 18

By the time of the revolution the processing of claims had “barely started”.

***

NOTES:

14- Cited in: Dirk Vandewalle “Qadhafi’s ‘Perestroika’: Economic and Political Liberalisation in Libya,” Middle East Journal, 45. 2 (Spring 1991): 220.

15- Dirk Vandewalle, “Qadhafi’s ‘Perestroika’: Economic and Political Liberalisation in Libya,” Middle East Journal, 45, 2 (Spring 1991):227.

16- Economist Intelligence Unit, Yearly Reports on Libya, cited in Vandewalle, “Qadhafi’s ‘Perestroika’,” 228.

17- UNHCR, Housing, Land and Property Issues, 26.

18- Ibid, 28.

***

The Authors

Mary Fitzgerald is a journalist and analyst specialising in post-Qaddafi Libya. She has reported from Libya since February 2011 for media including the Economist, the BBC, Foreign Policy, The New Yorker, the Financial Times and the Guardian. She lived in Libya throughout 2014. She is a contributing author to The Libyan Revolution and Its Aftermath published by Hurst/Oxford University Press.

Tarek Megerisi is a political analyst and consultant specialising in Libya and the wider Middle East. He has worked closely in an advisory capacity on Libya’s post-revolutionary transition with Libyan political bodies and international organisations. Currently based in London, he has contributed commentaries on Libya to the Carnegie Endowment’s SADA centre, Italy’s Limes magazine, Muftah magazine, and the Fair Observer among others.

***

The Contributers

Rhodri C. Williams is the Rule of Law Program Manager for the International Legal Assistance Consortium (ILAC). Based in Stockholm, Williams coordinates a large, integrated set of rule of law programs supporting partners in seven countries of the Middle East and North Africa region. Prior to working for ILAC, he worked for ten years as a consultant on humanitarian, human rights, rule of law and transitional justice issues in fragile and post-conflict settings such as Bosnia, Cambodia, Colombia, Cyprus, Georgia, Kosovo, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Serbia and Turkey.

Peter van der Auweraert works as Head of the Land, Property and Reparations Division at the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Geneva, Switzerland. He has worked on rule of law, post-crisis land and victims’ reparations issues in a number of countries and was part of a small UN-team engaged in mediation on land and property issues among local political actors in Kirkuk, Iraq. Prior to joining IOM, Peter Van der Auweraert was Executive Director of Avocats Sans Frontières (ASF).

________________