By Amelia Smith

At 3am, two weeks after he spoke out in a meeting against members of the ruling Popular Front for Democracy Party, security forces entered Mohamed’s house, beat him up in front of his mother and his wife and accused him of trafficking people out of Eritrea.

Mohamed was taken to a prison in Hashfayrat, located in a closed military zone roughly 30 kilometres from the city of Keren, where he stayed for around a year. He had problems with his eyes, was denied medical treatment, and wasn’t given adequate food to eat.

Eventually he bribed a military officer to liaise between himself and a smuggler to help him escape. The officer bought clothes and dates and distributed it between Mohamed and the other prisoners. On one of his shifts he pretended to be distracted and moved far enough away so they could escape.

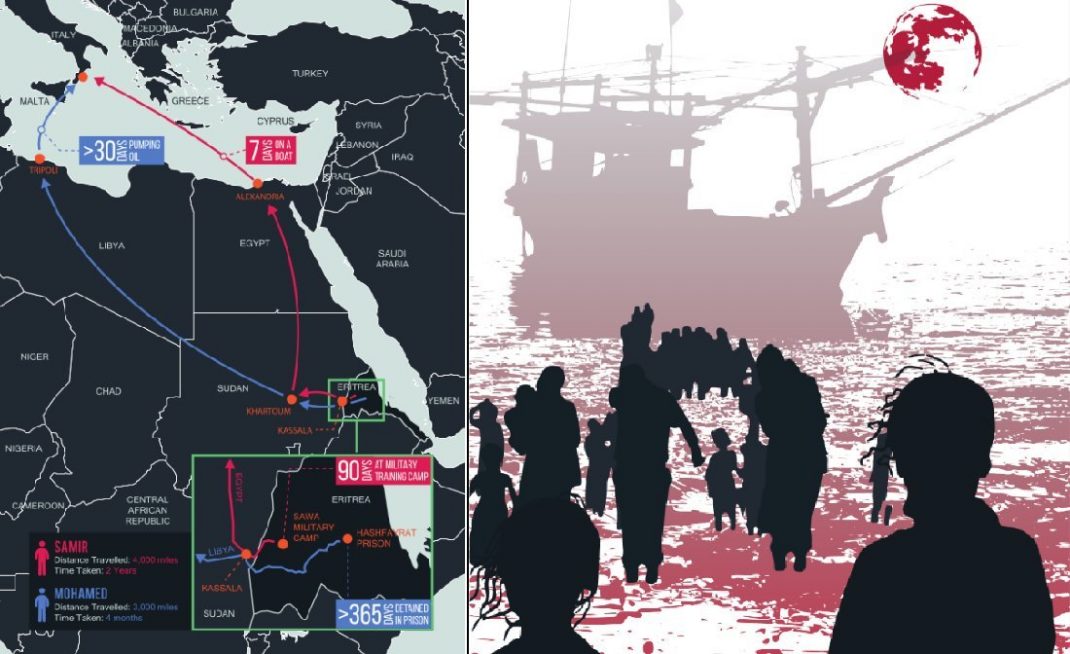

It was February 2014 and Mohamed and his fellow detainees spent seven days walking before they crossed the border and reached Kassala, a city in the eastern part of Sudan along the border with Eritrea. He remembers farmers tending to their cattle who took them in, gave them yoghurt and a place to rest.

Like thousands of other Eritreans who make this journey Mohamed avoided the UNHCR camps along the border – he had heard members of Eritrea’s infamous intelligence service regularly infiltrated the camps, picked people up and escorted them home where they would be tortured or killed.

The North Korea of Africa

Thousands of Eritreans each year make a similar journey to Mohamed’s to escape human rights violations at home. Isaias Afwerki’s brutal one-party state has seen the east African country labelled “one of the world’s most oppressive governments,” and the “North Korea of Africa”.

Eritreans are one of the most common nationalities aboard the ships attempting to reach Europe because the regime exerts control over the media and the judiciary and uses torture, arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances and other crimes against humanity as a method of instilling fear and implementing control among the people.

One of the regime’s most brutal collective punishments is indefinite conscription that males and females enter at the age of 18, rarely emerge from until at least a decade later and get paid next to nothing for.

In the mid-nineties the Eritrean government made military service compulsory for 18 months though service far exceeds this timescale. This enforced conscription has broken up the family unit, says Adam Al-Haj Moussa, founder and Secretary General of the opposition party the Eritrean National Front for Change (ENF), and forced convention on its head. So whilst young adults get old training as soldiers, their elderly parents are forced to become the breadwinners.

It’s not just a decent wage they miss out on. Conscripts are tortured, abused and the women subject to sexual violence. They receive no higher education and struggle to marry because they don’t have any money.

In 2016 a United Nations Commission of Inquiry found that the conditions of national service in Eritrea equate to the crime of enslavement.

Eritrea is nestled in the Horn of Africa, flanked by Ethiopia to the south and to the south east but it is what lies on the country’s western border that is of most interest to refugees. Sudan, the gateway to Libya, which, if they are successful will eventually lead refugees to their final destination: Europe.

In the anthology Refugee Tales II the writer Neel Mukherjee tells the moving story of Salim, an Eritrean from the capital Asmara who made this journey after being conscripted into the army in 1996 and sent to fight the Eritrean-Ethiopian war .

When he questions how long he will be in the army Salim’s commander throws him in an underground prison along with 400 other detainees. Eventually they dig a tunnel, escape, are shot at and walk for a month before arriving in Sudan.

To try and stop people like Salim leaving Eritrean authorities imported 350 wolves from Sri Lanka, installed cameras on their collars, and spread them across the border between Eritrea and Sudan to attack people trying to escape.

Yet despite brutal attempts to stop them thousands of Eritreans continue to make the perilous journey across the border each month.

By the end of August 2017, 112,450 Eritreans were registered as refugees and asylum seekers in Sudan. Like Mohamed many Eritreans arriving in Sudan avoid the camps – if they can escape being escorted there by Sudanese soldiers – so the number is likely to be far higher.

According to UNHCR’s latest figures some 7,165 Eritreans have entered Sudan so far this year but only 2,377 have registered as refugees and asylum seekers.

The Eritreans that bypass the camps for the cities have better access to services and jobs. Whilst it’s easier for Eritrea’s Muslim population who already speak Arabic – one of Sudan’s official languages – many still face hostility among the local population in a familiar story for refugees all across the world.

Eritrean refugees are blamed for Sudan’s sluggish economy, a lawyer working in Khartoum told me; that there is not enough bread to go round or accused of bringing indecent behaviour across the border. This hostility, coupled with the fact that there are a lot of restrictions on Eritrean refugees, means they face harassment on a day-to-day basis.

Sudan’s main camp in east Sudan, Shagarab, has earnt the nickname little Eritrea. There are a number of reports detailing conditions inside – like camps all over the world it is overcrowded because To try and stop people UNHCR simply doesn’t have the funds to like Salim leaving Eritrean offer proper services and the refugees share authorities imported 350 already scarce resources with other people living in the area.

As the refugee crisis continues, and refugees in Sudan continue to compete with other crises across the world, this is likely only to get worse.

Refugees inside the camps don’t have access to proper education, health care, or a decent allowance to live on. The scale of the issue in east Sudan has become so overwhelming it has been labelled “protracted”; in other words it is complex, overwhelming and unlikely to be solved in the near future.

According to opposition leader Moussa it is the conditions inside the camps that have pushed refugees into the arms of traffickers: “As a result of this failure militias managed to infiltrate the camps and organise an illegal way of helping them escape.”

Onwards from Sudan

In the past a popular route used by traffickers to take Eritreans out of the camps and beyond Sudan’s borders was through Egypt where they would cross the rugged deserts of the Sinai Peninsula into Israel, a destination particularly in demand with the country’s Christian population.

According to a 2014 report by Human Rights Watch up until 2010 Eritreans passed voluntarily through Sinai but about half way through the year information emerged that people were being kidnapped from the camps in east Sudan by the notorious, armed, Rashaida tribe among others, who sold them on to Egyptian traffickers.

To aid them police and military intercepted escapees, returned them to their traffickers and waved them through checkpoints.

Refugees have detailed how Egyptian police shot at, and in some cases killed them, as they reached the steel fence along Israel’s border with Egypt.

Those held captive were kept underground, forced to give up the telephone number of a relative who was then pressured to pay a ransom – whilst listening to them scream – in exchange for their release. Sometimes people were sold on to other groups, then on again, the ransom increasing every time.

Eritreans have been raped, mutilated, given electric shocks and burnt in the attempt to extort money from their families.

Towards the end of 2011 Moussa discovered that there were roughly 200 Eritrean refugees being held by human traffickers in Sinai and 600 had been locked up in Egyptian prisons since the start of the Egyptian Revolution.

Kidnappers often demand extortionate sums, as much as $30,000. “This trafficking turned into an organ trade because people couldn’t pay that money,” says Moussa. “They started to kill these guys and take their organs, kidneys, eyes and teeth.”

Eventually, after pressure from human rights organisations, Egyptian authorities conducted a raid in Arish, the largest city in Sinai where, Moussa recalls, they found the bodies of Eritreans who were missing their kidneys, hearts, eyes and teeth.

This, combined with Egypt’s intense crackdown on armed groups and

activists in the Sinai Peninsula since 2013, has made it increasingly difficult for smugglers to traffic Eritreans there. “It was a big scandal,” says Moussa; “the UN couldn’t take care of the refugees, it turned into trafficking, which turned into organ trafficking; it was a disaster for the Eritrean people.”

There are people still willing to undertake the journey through Egypt – Samir 1 was one of them. Samir’s nightmare started in Eritrea when he reached twelfth grade and was transferred to the notorious Sawa Military Camp. Since 2003 the Eritrean government has stipulated that all pupils must complete their last year of secondary school in Sawa under military authority – which effectively is the start of their military service – whilst studying for the equivalent of their A Levels at the same time.

Samir remembers digging, cutting down trees and walking long distances to collect firewood. Despite the labour intensive work there was not enough food.

“I found the working and the training very difficult,” says Samir, “because I had a health problem. I told them after I arrived at the camp and I gave them papers to prove it but they told me they did not care about me and they forced me to do the military training and to work hard. I spoke with many officials about my problems; in response I was beaten”.

This abuse continued every day for three months and Samir was finding it hard to concentrate on his studies. When he heard from two other students they were planning to leave he convinced them to take him with them.

The same day, as they went outside to collect firewood, the three of them fled towards Sudan. As the sun rose the next morning they approached the border – but as they looked around them they were surrounded by Eritrean soldiers and intelligence; they dodged the bullets as they tried to run away.

“We ran in different directions,” recalls Samir. “One of my friends and me were caught. They beat us severely with sticks. Two soldiers were running behind our friend. After that we didn’t see him and we do not know what happened to him.”

Samir was taken to prison where he was detained for just over a year, without standing trial, and was beaten and tortured. Then he was taken in a lorry to another camp to undergo more military training.

It was May 2008, says Samir, and he made the decision for the second time that he would attempt to get to Sudan. Through his training with the military Samir learnt which direction to move in if he wanted to get to Sudan. He waited until it was dark, dressed like a hepherd and set out. After walking for a full night in the mountains he found real shepherds.

“I went and drank with them and told them I was from the next village,” Samir says, “and that I’d lost my camels. In this way I crossed the border into Sudan, into Kassala”.

Samir spent two months in Khartoum until one night someone came to him, instructed him to get ready to travel and bundled him into a minibus which took him close to the border with Egypt. From here he took another car. Some prefer this route, he tells me, because the desert between Egypt and Sudan is shorter than the desert between Libya and Sudan.

Samir made it to Alexandria, a city on Egypt’s northern coast. Forty of them got into a small fishing boat and travelled across the sea for eight hours until they arrived at a bigger ship, which was stationary. Other passengers told him they had already been waiting for two days.

Samir stayed on board the ship for another day until a small boat arrived and another group of people climbed aboard. Some were pregnant women, he recalls; as the captain informed them they were moving towards Italy some started praying, others were weeping.

The people on board were rescued by the Italian navy after seven days on the sea; from here Samir travelled through Paris and La Chapelle before arriving in the Jungle, the now-closed refugee encampment in Calais, a major port for ferries between France and England.

One day Samir and his friends got lucky – a parked lorry had been left with the doors open and they climbed inside. Eventually the lorry drove to the port where it was checked by customs officials who found his friend and took him out. They didn’t see Samir.

Now living in England Samir is studying, waiting for accommodation, and for his wife to join him: “It makes me very sad,” he says, “thinking about all the people and what the government are doing to them in Eritrea, and the problems they have”.

“It makes me feel very sad and it makes me feel stressed. Here I feel very happy and lucky that I am living in this country. For so many people they didn’t arrive, they drowned in the Mediterranean; some of them died in the Sahara desert of hunger.”

…

to be continued

***

Amelia Smith is a London-based journalist who has a special interest in Middle Eastern politics, art and culture. She is editor of The Arab Spring Five Years On.

_______________