By Adam Goldman and Charlie Savage

A former militia leader from Libya was convicted on Tuesday of terrorism charges arising from the 2012 attacks in Benghazi, Libya, that killed a United States ambassador and three other Americans. But he was acquitted of multiple counts of the most serious offense, murder.

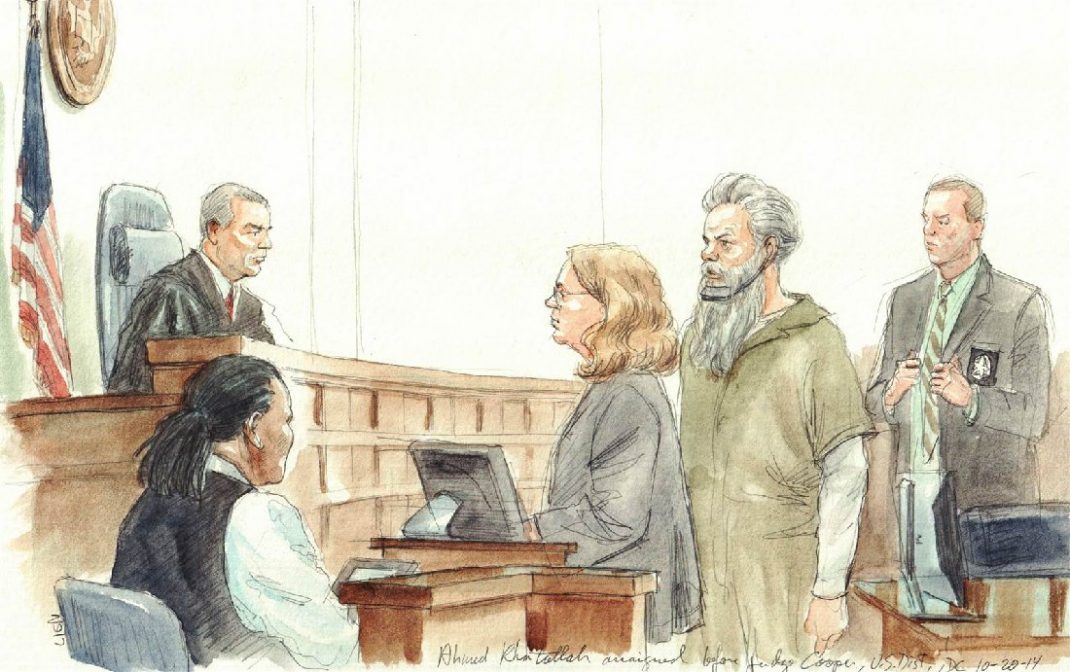

T he defendant, Ahmed Abu Khattala, 46, was the first person charged and prosecuted in the attacks, which took on broader significance as Republicans and conservative news outlets sought to use them to damage the presidential ambitions of Hillary Clinton, who was then the secretary of state. Yet the seven-week trial in federal court in Washington received relatively little attention from such quarters.

Mr. Khattala was convicted on four counts — including providing material support for terrorism, conspiracy to do so, destroying property and placing lives in jeopardy at the mission, and carrying a semiautomatic firearm during a crime of violence — but acquitted on 14 others. He faces life in prison.

The mixed verdict showed the difficulty of prosecuting terrorism cases when the evidence is not clear-cut. The outcome was reminiscent of the 2010 federal trial of Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, a Tanzanian man and former Guantánamo Bay detainee who was charged in federal court as a conspirator in the 1998 bombings of two American embassies in East Africa that killed hundreds.

Mr. Ghailani was acquitted of most of the charges, including each murder count for those who died, but he was still sentenced to life in prison for a conviction on one count of conspiracy.

Mr. Khattala, wearing a white shirt, betrayed no emotion in response to the verdict. Mr. Khattala’s attorney, Michelle Peterson, declined to comment after it was announced.

The trial included dramatic testimony from State Department and C.I.A. operatives who fought desperately to prevent militants from killing more Americans stationed in Benghazi.

On the night of the attacks, armed men overran the diplomatic compound and set fire to it. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and another State Department employee, Sean Smith, were killed. Hours later, militants attacked the nearby C.I.A. base with mortars and small-arms fire. Two C.I.A. security contractors, Tyrone S. Woods and Glen A. Doherty, were killed, and others were wounded.

The unusual circumstances of the crime and the evidence — an orchestrated, military-style assault in a near-failed state — were a challenge for federal investigators and prosecutors. The government showed the jury large amounts of surveillance video from the attacks, but Mr. Khattala did not show up inside the diplomatic compound until the fighting was over.

Prosecutors acknowledged that no evidence existed that Mr. Khattala had personally fired any shots or set any buildings ablaze, but argued that he had nevertheless helped orchestrate the attacks and aided them while they were underway. To make that case, they drew primarily on testimony from three Libyan witnesses and on a database said to be Mr. Khattala’s cellphone records.

Prosecutors presented witnesses who said that leading up to the attacks, Mr. Khattala had talked about the need to get rid of what he saw as an American spy base in Benghazi, and gathered weapons with his militia a few days beforehand.

Prosecutors said that he showed up outside the diplomatic mission before the assault there began, that he had been in phone contact with several of the attackers who were part of his militia — a prosecutor, Michael DiLorenzo, called them part of his “hit squad” — and that afterward he had expressed frustration that another militia leader had prevented him from killing more Americans as they were evacuated.

Defense attorneys, however, sought to raise doubts among jurors about whether Mr. Khattala had really played the role of on-site commander. They portrayed the phone logs as murky, while also stressing that those same records, if credible, suggested that Mr. Khattala had gone home hours before the mortar attack on the C.I.A. annex.

They also questioned whether it was really possible to identify who was in blurry surveillance video. And they portrayed the government’s Libyan witnesses as liars and con men who were probably making up their stories because they were Mr. Khattala’s enemies and because the United States paid them. In closing arguments, Ms. Peterson called the prosecution a “house of cards,” adding, “There are any number of reasons to doubt in this case.”

Prosecutors, however, also hedged, telling jurors that the evidence as a whole was sufficient to find Mr. Khattala guilty, both as a conspirator in the attacks and as someone who aided and abetted them as they unfolded.

“We don’t have to prove he was a commander,” Mr. DiLorenzo said at one point. “Even if he was a lookout, that was aiding and abetting. But this tells us what he was truly doing was being the on-scene commander.”

Emotional overtones complicated the assessment of the facts. Ms. Peterson told the jurors that prosecutors were trying to manipulate them, such as by calling witnesses who dwelled on the tragic details of the attacks — though the defense did not contest that material — and by subtly invoking feelings of tribal nationalism, like referring to “our” ambassador and compound.

During the rebuttal phase of closing arguments, another prosecutor, Julieanne Himelstein, frankly embraced that strategy, delivering a passionate appeal to the jury to hold Mr. Khattala responsible for the deaths of four men she described as “our son” and an “American son.”

Calling Mr. Khattala “a stone-cold terrorist,” she reminded the jury of video showing attackers stomping on an American flag while rampaging in the compound and, pointing at the defense table, declared, “How dare you!”

Mr. Khattala, with a long gray beard, remained stolid, as he had throughout the trial.

Although the jury was apparently unpersuaded that Mr. Khattala should be held responsible for the later attack on the C.I.A. annex, Mike Pompeo, the C.I.A. director, emailed staff about the convictions, saying that “a small measure of justice was meted out.”

In part because Mr. Khattala’s four convictions could be enough to keep him imprisoned for the rest of his life, it was not clear what consequences the 14 acquittals would have. Prosecutors are preparing to bring a second Libyan man to trial over the attacks, Mustafa al-Imam, who was captured in September and faces similar charges.

In 2010, supporters of using military commissions rather than civilian courts to prosecute terrorism cases seized on the mixed verdict in the African embassy bombings as demonstrating a purported failure of the civilian court system — but months later, Mr. Ghailani was nevertheless sentenced to life in prison. In the years since, meanwhile, the military commissions system has had difficulty bringing contested cases to trial, while several of its few convictions, from plea deals, were overturned on appeal.

The Obama administration refused to bring any new detainees to the wartime prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, where the military commissions system is operating. But a trial before the war crimes tribunal was probably not an option for Mr. Khattala. That system has jurisdiction only over members of groups with which the United States is at war, such as Al Qaeda, and while Mr. Khattala shared an Islamist ideology, scant evidence existed that he was a member of any such faction.

***

Adam Goldman is a Pulitzer Prize-winning American journalist. He received the award for covering the New York Police Department’s spying program that monitored daily life in Muslim communities.

Charlie Savage is the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. He is a Washington correspondent for The New York Times. He is also the author of “Power Wars,” published in 2015, an investigative history of national-security legal policymaking in the Obama administration, and “Takeover,” published in 2007, which chronicles the Bush-Cheney administration’s efforts to expand presidential power.

_____________