This report presents a city-based model of politics, economics, and for security. It describes a strategy for disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration.

This report presents a city-based model of politics, economics, and for security. It describes a strategy for disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration.

The report concludes with quotes from a recent report by the Libyan National Conference Process.

PART TWO

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

Libya has struggled severely since the U.N.-blessed and NATO-assisted campaign to protect Libyan civilians that led to the overthrow and death of Gadhafi in 2011.

It has teetered on the brink of becoming a failed state. Its hydrocarbon-based wealth, relatively small and mostly homogenous population of 6 million, and the relative weakness of its militias in areas beyond their immediate localities, have prevented the kind of complete humanitarian debacles witnessed in the current civil wars in Yemen and Syria.

Indeed, the violence in Libya since 2011, while tragic, has not been as unconstrained as in many other countries experiencing a breakdown of the state. But seven years after the death of Gadhafi, it is hard to detect any favorable forward movement toward stability—though there may now be a fresh opportunity, based on developments in recent months, as we discuss further below.

Libya matters to the United States, European countries, and the region for several reasons. The old adage that “what happens in Libya, stays in Libya” could hardly be further from the truth. Libya has been among the greatest sources of foreign fighters in the wars of the Levant this century.

It has been a major launching pad for cross-Mediterranean migration and human trafficking in recent years, as well. Its instability

can cause trouble for neighboring Tunisia, Mali, and Egypt (and vice versa). Its chaos has, and could again, allow possible sanctuaries and staging bases for terrorists who would strike the West. And now, it may also provide Russia opportunities for greater regional influence, including access to port facilities in the strategically vital Mediterranean Sea.

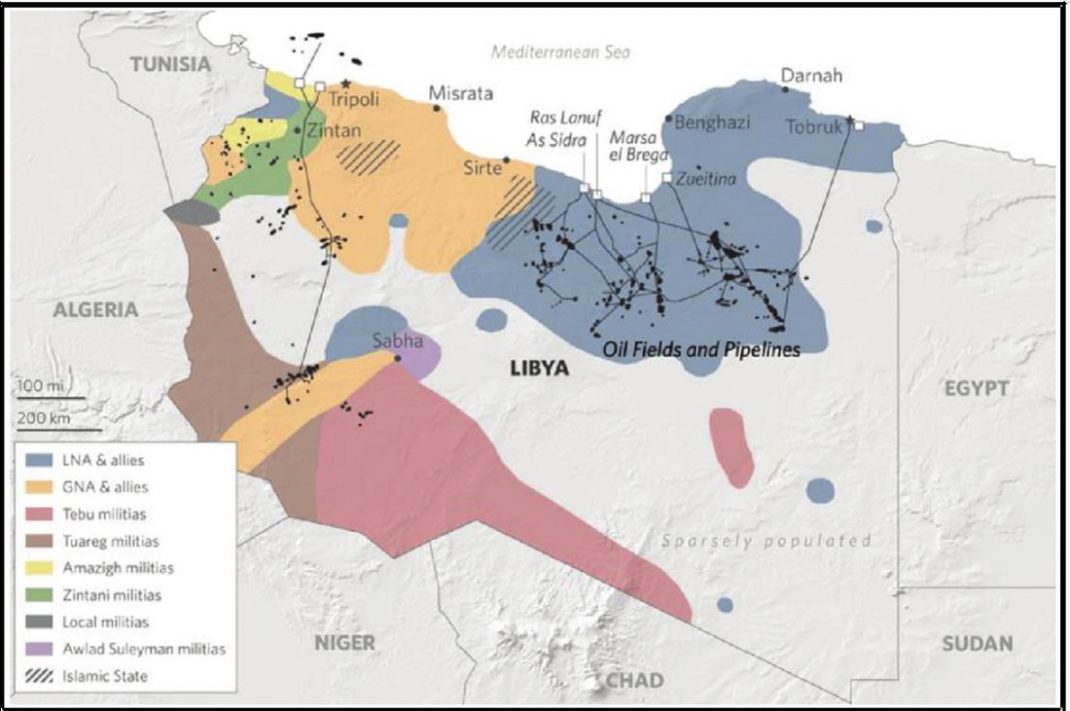

Within Libya today, the basic situation on the ground remains grim. There are two competing governments. They are dominated by at least four major political personalities, including:

_ Fayez Serraj, the head of the U.N.-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli;

_ Khalifa Hiftar, the leader of the “Libyan National Army” in Benghazi in the east;

_ Aguila Saleh, the head of the House of Representatives, which does not recognize the Tripoli government; and

_ Khalid al-Mishri, the head of the High Council of State (an advisory body to the main government in Tripoli).

Dozens of powerful militias control chunks of territory while competing for the spoils of the state—namely its oil wealth, critical infrastructure, and the smuggling opportunities provided by the black market, including human trafficking.

Fighting among these militias, and groupings of them sometimes called “super militias,” has intensified in recent months. There have been some ISIS and al-Qaida elements in Libya in recent years, too.

A U.N. mission headed by Lebanese statesman and Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) Ghassan Salamé, with the American diplomat Stephanie Williams as his deputy, is attempting to break the impasse by fostering national reconciliation and supporting Libyan efforts to devise a new governing formula.

A number of other countries play important but sometimes unhelpful roles as well.

Neighboring Egypt worries about the security of its western border and, to a degree, still fears Muslim Brotherhood dominance in Libya.

The UAE is motivated primarily by a desire to counter political Islamists and to block any inroads into Libya by its regional rival Qatar.

For its part, Qatar has economic interests in Libya and has been sympathetic to Libyan Islamists for both pragmatic and ideological reasons.

Turkey has also had long-standing economic ties in Libya, particularly to the port city of Misrata.

Italy and France cooperate and compete with each other in Libya. Both are interested in stemming refugee flows and ensuring access to oil. The former has a history of brutal colonial rule that continues to color Libyan perceptions. The latter has special interests, including counterterrorism, in a region that also includes several of its own former colonies.

Russia is engaging in Libya now as well, through outreach to Hiftar elements, among other activities. For all the complications that these foreign actors cause, it should, however, be noted that none plays the kind of deeply malevolent role that Iran has played in Iraq since 2003, or that Pakistan has played within Afghanistan over a similar time period.

Thus, there is a challenge, but there is also hope.

Libya was formed out of three major regions about a century ago. Later, Gadhafi deposed the nominal King Idris, who hailed from the eastern region previously known as Cyrenaica, and then ran a weak state for decades.

Gadhafi, from the city of Sirte (in the former Tripolitania region), played off different groups against each other and maintained enough combat power in a central army to mete out punishment and thereby enforce discipline when needed. Yet he kept most institutions underdeveloped, and other political actors weak, such that when he fell, little was left standing.

Multiple smuggling economies also characterized Gadhafi’s rule, with Libya’s southern border largely uncontrolled—even if the harshness of the terrain meant that only professional smugglers could be successful.

These included networks involved in the extensive smuggling of migrants from other African countries needed to perform jobs that oil-rich Libyans would not take.

Tens of thousands of migrants entered Libya yearly, with some 2.5 million living and working there as of 2011, often subject to exploitation and state punishment.

Prisons sometimes served as lucrative sources of rented, forced labor. Such exploitation of migrants as well as other smuggling economies became widely normalized and entrenched in local communities.

After Gadhafi’s overthrow, revolutionaries constructed a glamorized and incomplete narrative of having led a successful indigenous revolt against an evil dictator.

The narrative neglected NATO’s key role, ignored the rivalries between various competing tribal groups and militias, and in general created a false sense of confidence among Libyans that they could handle their own problems going forward.

These views, along with traditional Libyan suspicions toward outsiders, produced a general unwillingness among Libyans to request or accept outside help—a problem reinforced by the West’s unwillingness to offer much support at that moment in any event.

Indeed, Western nations ignored the hard-learned lessons of Iraq and Afghanistan: Toppling governments is relatively easy, but standing up functional and acceptable governance is excruciatingly hard, especially in states where earlier periods of autocracy prevented the development of strong institutions or traditions of self-rule.

Other key mistakes were baked into post-Gadhafi Libya. Municipal and parliamentary elections were organized in 2012, but they only served to sharpen divisions rather than unite the nation.

The resulting parliament quickly fell prey to militia pressure and many Libyans viewed it as dysfunctional. The tragic murder of the U.S. ambassador and other Americans in Benghazi in September 2012 led to a further reduction in any meaningful American engagement in Libya.

Differing views among key European and Middle East powers over which groups to favor exacerbated rivalries. An attempt to create a national army in 2013, the General Purpose Force, collapsed because of political divisions, opposition from militias, and inadequate institutional structures to absorb and retain new recruits.

Most training and arms wound up reinforcing the militias rather than national institutions.

Over the last five years, a strong actor, Khalifa Hiftar, has emerged in the country’s east. But even there, his rule is not universally accepted, and in general throughout the country, anarchy has reigned as before.

In Tripoli, a conglomerate of militias has effectively captured the state, enriching themselves through black markets in currency and consumer goods.

Through a U.N.-brokered process, a new Government of National Accord in Tripoli was created in late 2015 that was supposed to bridge the divisions between Hiftar’s camp and his opponents. Yet that government has failed to gain minimal legitimacy, even in western Libya, and Hiftar and his allies have opposed it.

Outsiders certainly share in the blame. Beyond the general disinterest in helping to build a post-Gadhafi Libya, the international community—including the United Nations, until Ghassan Salamé’s arrival as SRSG in mid-2017—has in general focused excessively upon the Libyan political process at the expense of other issues.

It has done so in the belief that if Libya’s civilian leaders reached a political agreement, the country could be stitched back together again. However, this assumption ignores two important realities that need to be addressed.

First, all of the current political leaders have vested financial interests in the status quo. Any one of the “big four” (Hiftar, Serraj, Saleh, al-Mishri) will become a spoiler to a potential political agreement if he sees his interests at risk.

Second, the focus on the political process assumes that an agreement among civilian leaders would lead to compliance by militia leaders, when the balance of power is in the favor of the latter.

The militia leaders are not only more powerful, in many cases they are seen by local constituents as more legitimate.

Those militia leaders, too, are profiting from the status quo financially, making them unlikely to be agents for change. Yet they also may not be dogged opponents of change, if a new system of economic and other incentives addresses their core interests.

Unlike most malevolent actors in other parts of the broader Middle East, they generally do not have intensely ideological, sectarian, or revolutionary motivations. At the same time, it is important not to legitimate violence, or whitewash the past criminal behavior of groups only paying lip service to the idea of reform.

Close vigilance is required, and the oversight board discussed above needs real independence, teeth, and the courage to act.

In terms of counterterrorism, the United States and its partners have improvised, with some success. They have made progress against the Islamic State “province” in Libya, forcing it to relinquish the territory it once controlled in and around Sirte.

In addition, often with U.S. support, Libyans ejected Islamic State fighters from Derna, Sirte, Benghazi, Tripoli, and other parts of Libya, forcing the Islamic State underground.

At times, the United States conducted unilateral operations; at others, it worked with the recognized government of Libya. In additional cases, rival forces (often working with U.S. partners such as the UAE or Saudi Arabia) took on the jihadists.

In still others, the United States worked with groups like Bunyan al-Marsous that are notionally “aligned” with the recognized government but operate independently. Similarly, in Tripoli, the Salafist-oriented but government-aligned Special Deterrence Force has aggressively gone after the Islamic State presence, while at the same time expanding its own political and economic power.

Open source data on the level of training, financial aid, and other assistance given to anti-Islamic State militias in Libya is scarce. However, as the above litany underscores, this rather opportunistic approach to counterterrorism risks making the militias stronger relative to the central government.

In addition, it further delegitimizes the recognized government, showing yet again that it does not control its own territory and that outside powers will simply bypass the government when convenient.

And to the extent that the militias engage in abusive, predatory, rapacious, and discriminatory activity, they delegitimize the political process even as they entrap local populations in narrow patronage networks. Over time, such grievances could become sources of renewed violent conflict.

Despite it all, there is now a moment of hopefulness and possible opportunity in Libya. The outbreak of militia fighting over Tripoli in September 2018 illustrates both the fragility of the current situation and the potential for international leadership to help the Libyans move forward.

Seizing the September 2018 security crisis as an opportunity, SRSG Salamé built a consensus around agreements to establish a cease-fire, began to adjust security arrangements for Tripoli, and wrested at least a verbal commitment from all but one of the militias to withdraw from key national facilities (and, at least in principle, eventually to disband).

While implementation has been slow to date, and is far from assured, the alacrity with which most political and military leaders in Tripoli accepted Salamé’s proposals demonstrates the Libyan understanding that the status quo is unsustainable—as well as increased willingness for international involvement.

In addition, prodded by Salamé, Serraj and Central Bank Governor Sadiq al-Kabir transcended their differences to agree on exchange rate reforms and a modest reduction in fuel subsidies. As a result, the cost of commodities went down substantially in ensuing weeks. The dinar strengthened against the dollar from roughly 7:1 to 5:1.

Letters of credit worth more than $1 billion were soon issued, with commodities beginning to flow in. The market is now operating more freely and the militias have shrinking access to the parallel currency market.

These steps could reduce the ability of militias to exploit certain black markets to entrench their positions.

Serraj also reshuffled his cabinet. While the national political stalemate persists, what happened in Tripoli in September 2018 demonstrates that with international engagement, improvements in the situation are possible.

A national conference to be held in Libya in 2019 could provide general guidance on everything from a new constitution for the country to eventual countrywide elections and other matters. Much of this is promising as well.

…

to continue in Part 3

***

(*) The group of scholars are: John R. Allen, Hady Amr, Daniel L. Byman, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Jeffrey Feltman, Alice Friend, Jason Fritz, Adel Abdel Ghafar, Bruce Jones, Mara Karlin, Karim Mezran, Michael E. O’Hanlon, Federica Saini Fasanotti, Landry Signé, Arturo Varvelli, and Frederic Wehrey.

________________________