Between people power and state power

By Frederic Volpia & Ewan Stein

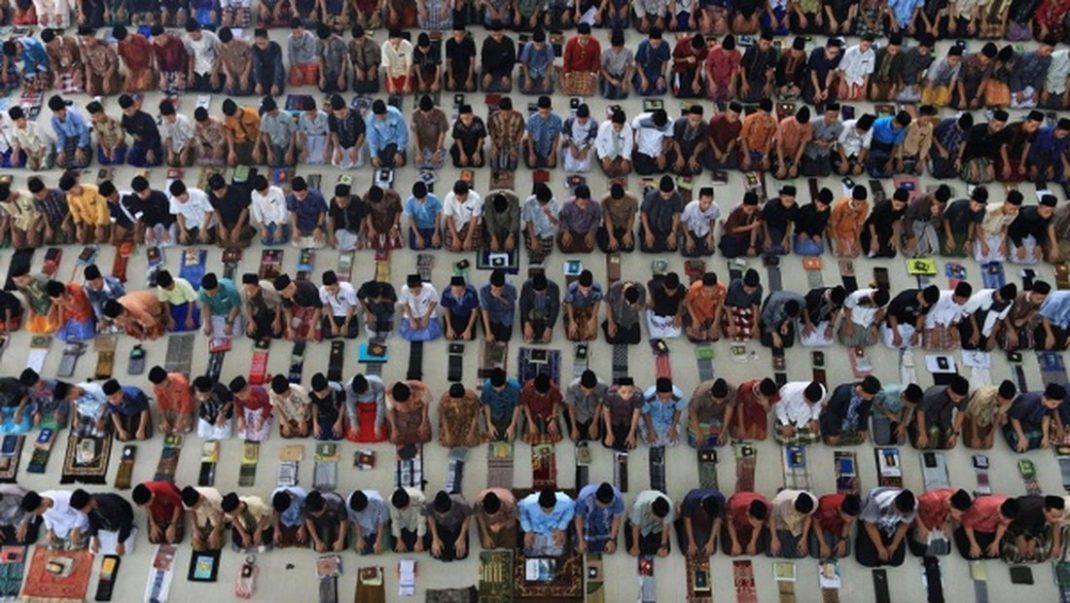

This paper examines the trajectories of different Islamist trends in the light of the Arab uprisings. In the following section, we track the evolution of statist and non-statist Islamist activism in the region in light of changing state dynamics.

This paper examines the trajectories of different Islamist trends in the light of the Arab uprisings. In the following section, we track the evolution of statist and non-statist Islamist activism in the region in light of changing state dynamics.

PART FOUR

4.2. Non-Statist Islamism and the uprisings

The post-2011 trajectories of salafis and jihadis in the countries of the Arab uprisings are also tied to both the general political evolution of the different states, and in particular to the success and failures of their statist Islamist rivals.

However because jihadi actors do not primarily have a state-centric agenda, their local engagement varies according to circumstances, from the deterritorialized mode of action of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb to the centralized control of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Regionally, two main post-uprisings developments strengthened the jihadi trend, which was briefly deemed to fall into irrelevance at the time of the uprisings. First, the multiplication of civil conflicts and the reduction of state capacity (Syria, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Yemen) has increased the number of locations and of potential recruits for armed jihadism.

Jihadi operations moved to those areas where armed resistance against the state seemed possible, legitimate and effective. Thus at the beginning of 2012, pre-existing jihadi networks in North Africa, particularly AQIM, redirected their efforts southwards towards Mali to join the challenge to the Malian state led by returning Tuareg from Libya.

In the North African context, the disorganization of the security apparatuses of the old authoritarian regimes allowed them to operate more freely. Similarly, in Syria, Al Qaeda-supported Iraqi networks redeployed themselves on the Syrian battlefield to oppose Asad’s government (and more secularized rebel groups) by creating the al-Nusra front.

In conflict zones like Syria and Iraq, salafis and jihadis are more directly creating structures of popular inclusion – albeit on a divisive sectarian basis – as the state institutions are unable or unwilling to do so.

This is indicative of the continued weakness of the state post-uprisings (despite it being “hard” and “fierce”) as well as the limited abilities of the statist Islamist parties to incorporate mass constituencies in such circumstances.

There is evidently a causal relation between the ongoing violent confrontation between authoritarian state elites and statist Islamists and the reduced ability of both to address satisfactorily issues of mass inclusion.

When it is in control of territories, jihadism has proven to be an effective, and fairly economical, ideological and legal resource for groups seeking to enforce obedience and conformity among fragmented or traumatized communities, such as in the case of state weakening or collapse.

The appeal of the jihadi model may relate to its simplicity and the ease by which it may be “rolled out” in different contexts.

Even if the leaderships of groups like the Islamic State and Ansar al-Sharia (both in its Yemeni and Libyan declinations) are not “organic” to the populations they seek to rule, they can garner consent by striking deals with (i.e. “buying off”) tribal and other local authorities, appealing to disaffected Sunni youth and enforcing a recognizable – even if not welcomed – legal regime.

The case of ISIS illustrates the evolution from infra-politics to the transnational politics of jihadism when the constraints of state control are relaxed.

The organization is primarily concerned with, on the one hand, the micro-management of societal issues through religious regulations and, on the other, sustaining its capabilities to wage transnational warfare against opponents of their creed.

The transnational dimension of jihadi activism has also been strengthened by a particular regional combination of successes and failures of democratization after the Arab uprisings.

The failure of democratization and the failure, apart from in Tunisia, of statist Islamism of the Muslim Brotherhood “brand”, amidst the Syrian conflict and the Egyptian military coup have ensured the continuing relevance of a jihadi ideological discourse, which had been threatened when it appeared Islamist movements could gain power democratically.

In 2014, with the rebirth of ISIS and the sectarian conflict in Iraq and Syria, the ideological attractiveness of jihadi discourses may also have increased.

The transnational and regional dimension of jihadism in connection with the post-Arab uprisings conflict goes well beyond the countries of the Arab uprisings themselves.

In addition to the circulation of jihadists within the Arab world, “foreign fighters” are increasingly drawn from Muslim populations based in Europe.

Such dynamics, which are actively promoted by jihadi movements, illustrate that they are not solely the product of failures of democratization in the Arab world but reflect wider problems of social and political inclusion and alienation.

This means that states not currently in the throes of civil war will not necessarily escape jihadist or salafi activism. Across the region the salafi trend continues to act as a refuge for political (or armed) activism in the countries of the region for different reasons in both democratizing and non-democratizing countries.

In Egypt the increase in repression and political blockage following the military coup has inexorably pushed would-be political activists back into either pious withdrawal or, for some, violence.

In Tunisia, the rapid rise of Ansar al-Sharia in a context where an Islamist-led government was in charge of the country illustrated the dissatisfaction of many of the actors of the revolution (particularly the unemployed urban youth) with the slow pace of change and the pragmatic political approach taken by Ennahda.

Thus, even in a context of strengthening and democratizing state institutions – that is in “successful” democratic transitions – the uneasy process of turning revolutionary citizens into “well-behaved” voters ensures that those constituencies that still feel excluded and/or unhappy from the dominant political consensus can find alternative avenues of inclusion via non-statist Islamist movements.

Conclusion

The different embodiments of Islamism in the region, their successes and their failures, track the rise and fall of different models of governance far more than they follow the fate of particular regimes.

It is the degree and nature of transformation in state-society relations, through the formal and practical positioning of Islamist parties, that directly influence the evolution of post-uprisings Islamism.

As O’Donnell and Schmitter already noted regarding the democratic transitions of the 1980s, the plasticity of identities is a crucial component of the political process during such transitional periods.

Because of historical trajectories, some Islamists movements faced a more arduous task than others in reinventing themselves and in contributing to an overall transformation of the political ethos in the post-uprisings situations.

Thus Ennahda in Tunisia, with its well-considered reformist approach, its non-conflictual relations with a weakly politicized military, and organizational superiority over an emerging salafi movement was better placed than the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt (or in heavily militarized and fragmented Libya and Yemen).

This does not necessarily mean that the former was bound to succeed and the latter bound to fail, but rather that the strategies devised by each actor were crucial in tipping their countries towards or away from democratic consolidation.

When, as in Tunisia, Islamist parties participate in a working multiparty system, accompanied by an increase in civil liberties, they can contribute to democratic consolidation, stability and enhanced state governance.

Where Islamist movements are violently excluded, as in Egypt after the 2013 military coup and the ban on the Muslim Brotherhood, the opposite results.

…

to be continued

***

Frédéric Volpi is Deputy Director of the Institute of Middle East and Central Asia Studies and Senior Lecturer in International Relations at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of a number of books on political Islam and democracy in the Muslim world, and is coordinator of the BRISMES research network.

Ewan Stein – Senior Lecturer in International Relations. His research interests include the international relations of the Middle East, particularly the role of ideology and intellectual dynamics, political Islam, and the politics and foreign policy of Egypt.

____________

University of Edinburgh