By Frederic Wehrey

To contain the coronavirus, Arab governments are mobilizing official Islamic institutions. The most pressing goal is to shut down sites of potential contagion as Ramadan approaches.

To contain the coronavirus, Arab governments are mobilizing official Islamic institutions. The most pressing goal is to shut down sites of potential contagion as Ramadan approaches.

.

Global Pandemic: Coronavirus and Global Disorder

As the new coronavirus and its economic and political consequences ripple cross the Arab world, Arab regimes are facing an extraordinary and possibly existential test.

Their public health capacities may be strained but so too will their economic resources and coercive institutions.

Moral suasion will grow increasingly important, even in the most repressive of states, to contain the outbreak and its economic and political fallout.

In this effort, Arab governments are mobilizing official Islamic institutions—namely, ministries of Islamic affairs and awqaf (endowments)—as well as engaging local clerics and Islamists.

The most pressing and critical goal is to limit the virus’s spread by shutting down sites of public contact and potential contagion including Islamic spaces, principally mosques but also religious schools, as well as events like pilgrimages and commemorations—especially as the holy month of Ramadan begins in April.

To ensure compliance with social distancing and other measures, many regimes are relying on national and especially local clerics who have gained citizens’ trust for their religious learning and social roles.

In tandem, Islamic charities connected to regimes are proving vital in alleviating the outbreak’s dire economic impact.

Enlisting Islamic authority in some countries may prove crucial in compensating for the public’s low trust in the regime’s information outlets and officials, which could have dire public health consequences.

As studies of past pandemics have shown, when trust and regime legitimacy is low, the public is more likely to engage in “skeptical noncompliance.”

Conversely, Islamic venues of communication may prove vital in convincing the public that an eventual end to the pandemic was because of the regime’s efforts, whether through its own actions or by facilitating international help.

Relatedly, Islamic authorities may in some instances accrue greater popularity by aligning themselves with robust government responses.

The pandemic arrived as several Arab regimes have been steadily consolidating their control over clerical establishments, often under the pretext of countering violent extremism.

These supposed reforms have included purges, arrests, edicts and legislation, new oversight bodies, and other measures.

These changes may now reap dividends for some governments, and, just as they instrumentalized the specter of terrorism, they may exploit this outbreak to exert greater control and surveillance over Islamic authorities.

Temporary emergency measures could become permanent, and ad hoc work-arounds by Muslim clerics, like conducting sermons or Quranic lessons virtually, could facilitate monitoring by the regime.

And yet Islamic institutions are hardly obsequious pawns of the rulers—they could also emerge from this pandemic with newfound privileges and social clout.

As intermediaries with local society, they have long had a better negotiating position than is commonly recognized—a position that might be strengthened by this unprecedented crisis.

Moreover, even in authoritarian and notionally stable states, like Egypt for example, clerics are not displaying a uniform response nor are religious institutions completely adhering to the government line.

Personal and bureaucratic rivalries have come into play, as have ideological fissures among various Islamic movements.

In war-torn and fragmented states, like Yemen and Libya, the rivalries are naturally starker.

Various religious actors, aligned with warring political factions, see this outbreak as an opportunity to undermine opponents in ongoing contests for public support and control over Islamic institutions.

Though the long-term fallout from this crisis is difficult to predict, it may affect cleric-state relations. Especially in rentier states like the Gulf monarchies, lower oil prices and the impending end of the rentier era itself might eventually strain states’ financial patronage and co-option of Islamic institutions and actors.

Though these states have reserves, they will likely face hard choices. As resources dwindle, they may permit or encourage clerical scapegoating, often on external sources to deflect from their own governance shortcomings.

There has already been an initial wave of such rhetoric, with some commentators framing the contagion as divine retribution for China’s repression of Muslim Uighurs or as a “Shia virus.”

As they have done in the past, some regimes may resort to a strategic deployment of sectarianism, including funneling oil revenues to favored communal groups or sects while neglecting or demonizing others.

For now, it is certain that the mobilization of Islamic institutions across the Arab region is varied and nuanced, reflecting different levels of state cohesion and societal polarization, regime legitimacy, religious diversity, coercive capacity, and economic resources.

These Islamic actors therefore serve as important windows into state-society relations in the Arab world—and how the pandemic’s effects may be reshaping those relations.

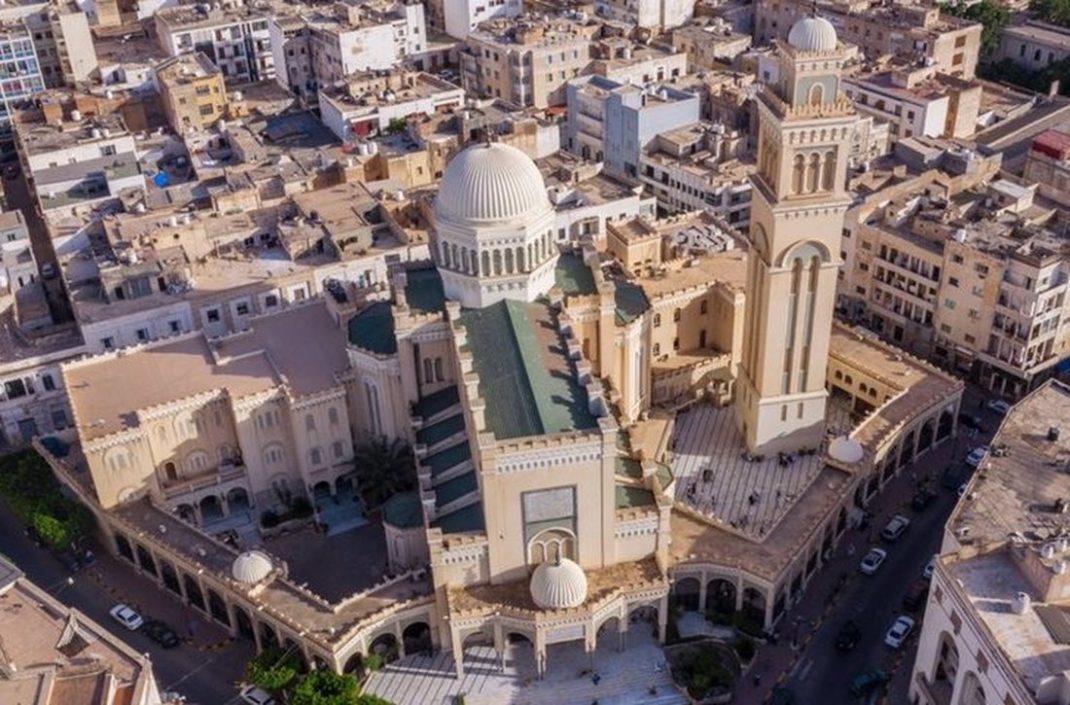

LIBYA

Like Yemen, Libya has been wracked by civil war, extreme political fragmentation, collapsing infrastructure, and international intervention.

Relatively few cases of infection have been detected so far, but like Yemen, this is because of a lack of testing—and the consequences of a contagion could be severe.

Thousands of displaced Libyans and detained migrants are uniquely exposed to devastation by the coronavirus.

An ongoing assault on the capital by militia forces aligned with Libyan Arab Armed Forces commander Khalifa Haftar has escalated to include attacks on hospitals and shelling of civilian areas.

On top of this, public health responses are obstructed by a worsening fiscal crisis and competing nodes of political and religious authority.

Within Libya’s opposing political camps—a Haftar-aligned administration in eastern Libya and the Government of National Accord (GNA) in the capital of Tripoli—there are opposing ministries of Islamic affairs and awqaf and mosque networks.

Each one influenced to varying degrees by a current of Salafism known as “Madkhalism” named for the Medina-based cleric Rabi bin Hadi al-Madkhali.

Both sides have tried to enlist the Saudi cleric’s authority for their respective causes, and each has issued public health notices regarding the current crisis.

Citing a speech by GNA Prime Minister Fayez al-Saraj as well as writings by Salafi scholars, the Tripoli-based Ministry for Islamic Affairs and Awqaf on March 16 urged people to stay in their homes and to stop daily and Friday prayers in mosques.

Meanwhile, in the east, the General Authority for Awqaf and Islamic Affairs issued a similar appeal on March 17.

The appeals were moreover complicated by challenges to the ministry’s authority, especially in the west. In one notable case, Tariq Durman, an influential Madkhali cleric hailing from the town of Zintan to the southwest of Tripoli, rejected the ministry’s order to cease mosque prayers—part of a long-running dispute between Durman and the ministry’s head, Muhammad al-Abbani.

Other splits include local awqaf offices that reject the Madkhali orientation of the Tripoli-based ministry.

Most significantly, this happened in Misrata (though the city does include an influential Madkhali current) and areas in western and eastern Libya where local Madkhali Salafi clerics follow a rival Saudi cleric, Muhammad al-Madkhali, who hails from the same tribe as Rabi bin Hadi al-Madkhali and who recently issued a statement on the virus.

In addition, adherents of Sufism have fiercely rejected the Madkhali Salafis’ efforts at dominance.

But perhaps the biggest religious-political rivalry that has affected public health pronouncements in western Libya is the rejection of the ministry’s mosque closure by Libyan Grand Mufti Sadeq al-Ghariani.

He leads Libya’s Dar al-Ifta (the state body responsible for Islamic legal guidance) and has long battled the Madkhalis for influence over mosques and the public space—a struggle that has been waged in the media and in sermons, but also through violence.

Commanding support from an array of revolutionary factions, Islamists, and some jihadists, al-Ghariani and his Dar al-Ifta lambasted the order to shut the mosques, arguing that there “is no proof in history of Muslim mosques being closed in an entire country,” while clarifying that people who fear viral transmission are permitted to stay at home.

He later argued that the virus and calls for a humanitarian ceasefire were a distraction from “the real epidemic” of Haftar’s “project.”

These themes were echoed in social media accounts affiliated with partisans of al-Ghariani and Libyan armed groups who have aligned with his movement, like supporters of the Benghazi Revolutionaries Shura Council.

But beyond such ideological disputes, there is another danger: that the various armed groups upon whom the authorities in both the east and west rely on to enforce order, as de-facto police, could use this public crisis to further entrench their power and social control.

This is especially pertinent in the case of the Madkhalis’ well-armed militias, who’ve already acted as morality police over public spaces in both regions, for example by shutting down mixed-gender gatherings and artistic events.

It seems likely, then, that no matter the pandemic’s course in Libya, the public health response will be hampered by not only severe limitations in medical and governance capacity, mounting economic problems, and political fissures, but instrumentalization by rival religious authorities and their affiliated armed groups.

***

Frederic Wehrey is a senior fellow in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His research deals with armed conflict, security sectors, and identity politics, with a focus on Libya, North Africa, and the Gulf.

__________

This research was conducted under a generous grant from the Henry Luce Foundation.