By Hussein Ibish

It has been a year now since the start of the current phase of the civil war in Libya has pitted eastern forces led by Libyan rebel national army chief Khalifa Haftar against western forces loyal to the national government.

It has been a year now since the start of the current phase of the civil war in Libya has pitted eastern forces led by Libyan rebel national army chief Khalifa Haftar against western forces loyal to the national government.

Agreement in Tripoli. Neither seems capable of a decisive victory, and with little prospect of peaceful reconciliation, the possibility of formal partition or ever larger informal rooms.

Both sides receive support from outside powers, for whom the competition for Libya is a struggle for regional natural resources and for the future of Islamist groups in the Arab world.

The ANL offensive which started a year ago has been called Operation Dignity; irony was one of the first victims of the war.

It was an attempt to extend control of the Haftars from the main eastern cities of Tobruk and Benghazi to the western coastal areas, and in particular the capital.

Because the fighting forces of the GNA include Islamist militias, Haftar launched his campaign as an effort to purge Libya of religious extremists and terrorists.

Tripoli has proven to be an elusive price for the Orientals. While the Turkish-backed GNA has been mainly on the defensive, Haftar is overwhelmed and never seemed likely to overtake capital or any of the other major western coastal cities.

Instead, as the battle has intensified in recent weeks, the ANL has taken over three strategic cities near Tripoli.

FNA al-Sarraj, Prime Minister of the GNA, also intensified rhetorical attacks on Haftar, ruling out any deal with the rebel commander.

Sarraj’s position was considerably strengthened by a major intervention by Turkey, which deployed its own troops in the conflict, as well as drones and other military equipment.

Ankara is said to have sent thousands of Syrian Islamist fighters to support the GNA and its allied Libyan Islamist militias.

The interest of turkeys in Libya is partly motivated by ideology. The Islamists associated with the GNA are among its last allies in the Arab world, along with Qatar, Hamas and various parties of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is reluctant to let another Sunni Islamist power in the Arab world collapse without fighting.

The authority of the GNAs is also crucial for Turkish ambitions in the eastern Mediterranean: Ankara tries to control the exploitation, and especially the distribution, of large reserves of liquid natural gas.

Having drawn an imaginary line from the north bank of Turkey to the coast of Tripoli, it claims joint control, with the Sarraj government and against the interests and objections of Greece, Cyprus, Israel and Egypt nearly a third of Mediterranean waters.

But even with Turkish support, the ANL is unlikely to come out of its Western redoubts. Haftar, like Sarraj, is the recipient of substantial foreign support and supplies, although perhaps not as intensive or direct.

The United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Russia support all of his efforts, with occasional Emirates and Egyptian air strikes against his enemies, and some Russian mercenaries fighting alongside his forces.

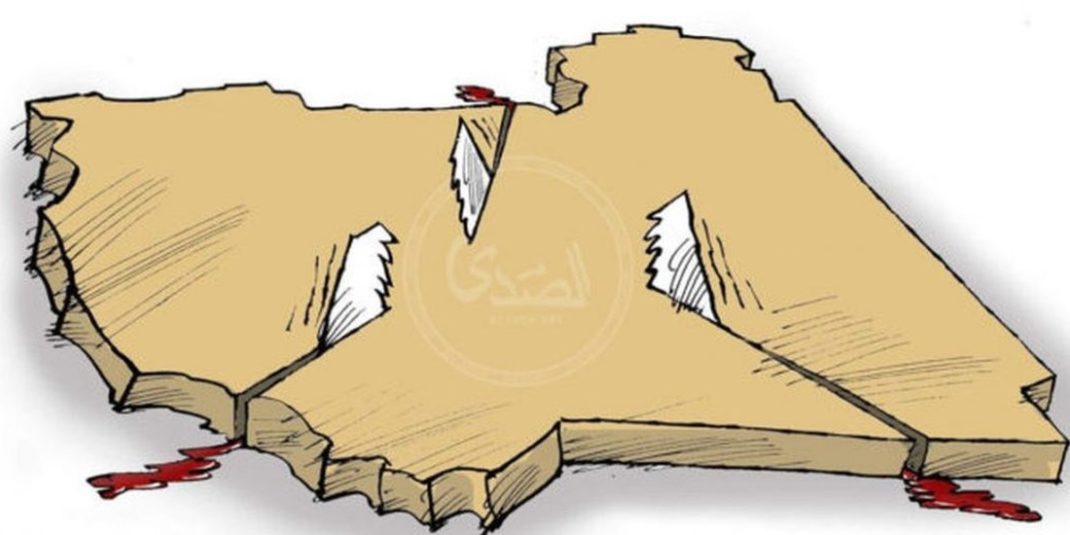

The impasse of the past year suggests that a de facto partition could develop between an Islamist-dominated western Libya, with the support of the Turks and Qataris, and the East controlled by Haftar, with the support of the Egypt and the Gulf.

A man who could have had the chance to unite the two parties lost his own fight against the coronavirus on April 5 in Cairo: Mahmoud Jibril, first Libyan Prime Minister after Gaddafi.

Jibrils’ most significant legacy could be his victory in the July 2012 elections in which his coalition of essentially secular political forces defeated the Islamist parties by emphasizing patriotism rather than religious fanaticism.

Jibrils’ political genius lay in his ability to wave the flag against the Islamists, without allowing them to deploy the Qur’an against him.

Indeed, he was able to use Islam itself to attack the Islamists, claiming that the Libyan people need neither liberalism nor secularism, nor false pretenses in the name of Islam, because the Islam, this great religion, cannot be used for political purposes. Islam is much bigger than that.

But despite all his skills, Jibril could not prevent his country from drifting into civil conflict. He could not fight the growing power of the independent militias and instead tried to contain them.

Some have condemned this strategy as an appeasement, but that may have been all he could find, especially since the international community, having looked away from Libya after the death of Gaddafi, did not couldn’t support him when he needed it most.

As his country fell into all-out conflict, Jibril, who was not a warlord, was expelled from politics and exiled to the United Arab Emirates and Egypt.

Libya, sliding to a partition between Haftar and Sarraj, could really use a Jibril right now. None are in sight.

***

Hussein Yusuf Kamal Ibish is a Senior Resident Scholar at The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. He was a Fellow at the former American Task Force on Palestine.

___________