By Daniel Hilton

Khalifa Haftar’s LNA used this western Libyan town to launch his assault on Tripoli. In its wake, MEE finds a traumatised place littered with mass graves.

Khalifa Haftar’s LNA used this western Libyan town to launch his assault on Tripoli. In its wake, MEE finds a traumatised place littered with mass graves.

.PART (I)

At the Haruda family’s farm, agricultural labourers have been replaced with forensic teams, their bright white protective suits silhouetted against dusty, rust-coloured soil.

Areas for excavation have been marked out in chalk, like macabre football pitches. Little triangular flags beside shallow potholes indicate each place bodies have been found.

Tarhuna, a rural town 60km southeast of Tripoli, where olive trees stripe low hills rising out of Libya’s coastal plain, is searching for its dead.

Almost 80 corpses have been pulled from the ground in two and a half months, 56 in the Haruda farm alone. Officials believe three times that number could still lie under Tarhuna’s fields and orchards.

“We still have a lot to dig. Just 20 percent of this area has been excavated,” says Mohammed Ali al-Kosher, the town’s mayor.

“People of all backgrounds were killed and buried here, including a 10-year-old child. We’re finding new bodies every day. One man was even buried with his car, his hands tied to the steering wheel.”

The teams searching for corpses look for tell-tale signs – a chemical change in the soil, mounds of earth piled up nearby, lingering smells.

In two graves from which bodies were retrieved the day before, blood and decomposed tissue has fossilised the victims’ outline in the earth. Forensic teams sieve the soil, finding fragments of bone and clumps of hair. The stench remains.

Tarhuna is traumatised, with emotional scars running far deeper than the crevices carved into the ground in the search for victims.

For 14 months this town of 40,000, whose fertile lands were once prized by Italian colonisers and favoured by Gaddafi, was transformed into a military base from which eastern commander Khalifa Haftar launched his ill-fated assault on Tripoli.

Hundreds of civilians were killed in the fighting around the Libyan capital between April 2019 and June 2020, but in Tarhuna people were disappeared for the smallest of infractions or suspicions of allegiance.

When Tarhuna was taken on 5 June by forces loyal to the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA), they discovered 106 bodies stacked up in the local hospital’s morgue.

Quickly, authorities realised the town held several mass graves, too. The Haruda farm is the largest of eight found so far, with search teams believing that number could rise to 12.

Kosher, who the GNA placed in charge of a temporary steering municipality after taking the town, says it will take at least a year to excavate all the suspected sites, particularly without better equipment and international support. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has called for a “transparent investigation”, but so far little assistance has been forthcoming.

“From a religious point of view, this is not a decent burial. This is what Daesh does, these are the actions of people who desecrate Islam,” Kosher says, staring into a pit where 11 bodies were recently retrieved.

“The killings were a message: even opposing the fighting in Tripoli can lead to death. This was all done with the blessing of Haftar and his allies.”

Tarhuna: Haftar’s launchpad

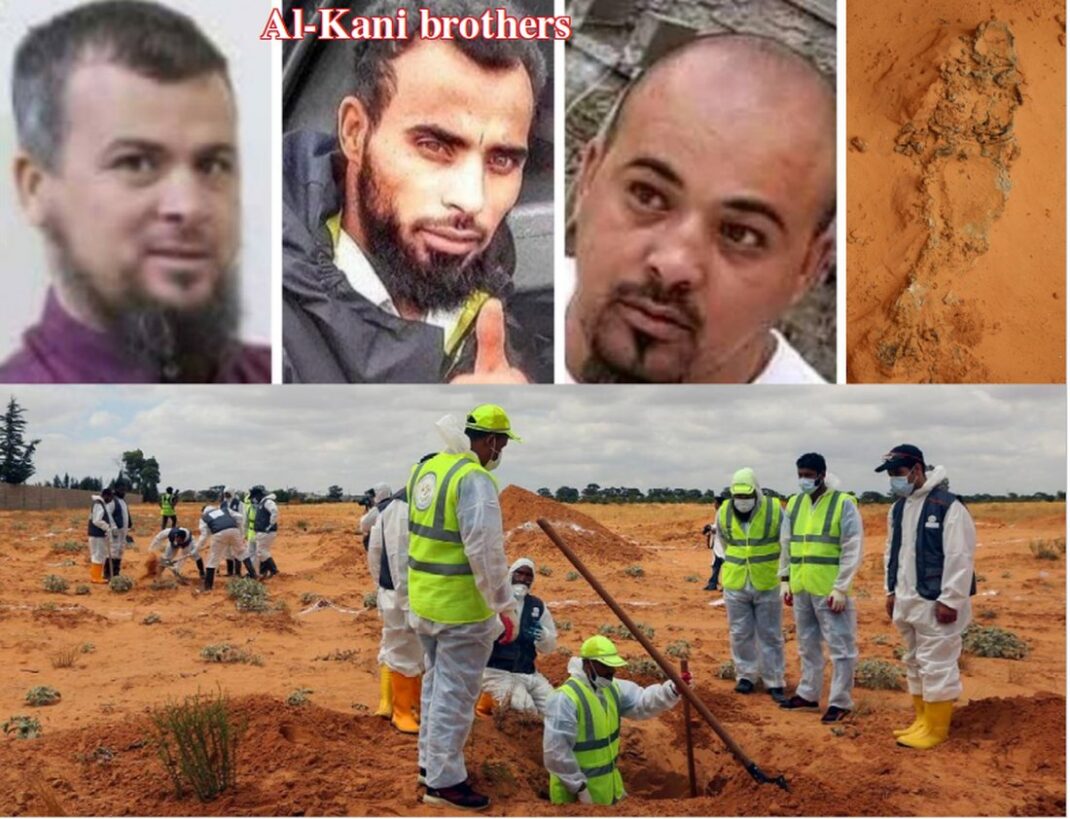

For five years, Tarhuna was ruled by a family of bloodthirsty brothers, the Kanis, and their eponymous Kaniyat militia, also known as the 7th Brigade.

Essentially mobsters, who in the tumult of post-Gaddafi Libya carved out a fiefdom in this western town, the Kani family momentarily gained geopolitical significance early last year, when Haftar sought to use their territory as a launchpad for his assault on the Libyan capital.

Haftar, a UAE, Egypt and Russia-backed warlord who commands a collection of militias known as the Libyan National Army (LNA), had long eyed Tripoli.

To his surprise, however, armed groups from Tripoli and Misrata rallied around the UN-recognised GNA with potency, and his offensive bogged down in the capital’s outskirts.

As the conflict progressed, Turkey poured drones, equipment and Syrian mercenaries into Libya, swinging the fighting decisively in the GNA’s favour until the LNA melted away in June this year.

During those 14 months, when Tarhuna was awash with LNA battalions and foreign mercenaries, Haftar’s Kaniyat allies became increasingly suspicious of the population they repressed, with disastrous consequences for the town’s residents.

Paranoia and conflict industrialised the Kanis’ murderous tendencies. Crackdowns on dissent – both real and imagined – became daily occurrences. Whole families disappeared at a whim.

Today, mementos of murder can be found in almost every neighbourhood, every farm.

Near a construction site yet to be probed for bodies lies a fridge, its inside caked in dried blood.

Elsewhere, a battered white car riddled with bulletholes has ploughed into some trees. To the side, two black shoes, a pair of high heels and a knot of hair in the mud are all that remain of its passengers.

Tarhuna’s now-bustling junctions were once the scenes of Kaniyat checkpoints, where LNA militiamen arbitrarily pulled men out of their cars for perceived infractions, never to be seen again.

One road by an open field, known as the “triangle of death”, was a favoured place for summary executions. Neighbourhoods on three sides could witness the killings.

Most of those found in the hospital have been identified, including children. But of those being pulled from the ground, just a couple, including a man in his 60s found dumped in a well, have been named.

The sheer volume of horror stories Tarhunis have to share is overwhelming: casual conversation can reveal a resident is missing several brothers, cousins or uncles. Hundreds of children now have no fathers.

There is palpable relief that the LNA and Kaniyat have gone, but suspicion – both of fellow Tarhunis and state institutions in general – is widespread.

According to the Tripoli-based General Authority of Search and Identification of Missing Persons, some 270 people are reported lost in Tarhuna.

But D Mohamad Ziltny, its international cooperation manager, estimates 150 more have yet to be reported, with fear of reprisals still hanging over the town.

Though the Kanis fled in June, their menace remains.

Residents complain of phone calls from the brothers, threatening retribution if their crimes are exposed and promising a return from exile in Libya’s Haftar-held east.

Rule of the Kani brothers

At first glance, Mohammed al-Kani does not resemble a warlord. The eldest, quietest, best educated of the seven brothers, he was the only Kani to hold down relatively well-paying jobs, in the security services and the state oil company.

Behind that calm veneer, however, was a ruthlessness and unpredictability. Supplicants could be as likely killed as have their requests accepted.

“He was the thinker. He came to be like a sheikh. Like Al Pacino in the Godfather, Mohammed was always thinking, as opposed to necessarily getting his hands dirty,” Jalel Harchaoui, an analyst and expert on Tarhuna, tells MEE.

“The other brothers were more into physical action, whilst Mohammed was the brains behind the operation. If you walk away from a conversation with Mohammed, you don’t walk away with the impression that you just spoke with a gangster, with hundreds of corpses beneath his feet.”

Beside him was Mohsen, a headstrong military man who headed Kaniyat assaults on Tripoli, both during Haftar’s offensive and in summer 2018, when the Kanis attacked the capital in a quarrel over state revenues.

Demanding, independent and contemptuous of his LNA colleagues, Mohsen proved a headache for Haftar, taking the warlord’s weapons but refusing his orders.

That tension has contributed to suggestions that his September 2019 killing, the circumstances around which remain murky, was facilitated in part by LNA elements. His death, alongside a younger brother, was met among the Kaniyat with a howl of rage that saw dozens of detainees executed in retribution.

The man leading the crackdown at home was Abdul-Rahim al-Kani, whose role in Tarhuna is likened by Hachoui as heading the mukhabarat, or secret police.

A shaven-headed enforcer, Abdul-Rahim’s task was to maintain the Kanis’ increasingly unsure position in Tarhuna as the Tripoli offensive dragged on.

The Kanis drew their wealth from multiple sources: a cement factory, agricultural assets, skimming money transferred by Tripoli to the municipality. They also enforced a protection racket, practiced extortion and ransomed people seized almost at random.

But like the mafia they were, the Kani also played the role of benefactors, handing out favours and endowments to Tarhuna residents struggling in Libya’s collapsed economy.

Between 2015 and the moment it joined the LNA, the Kaniyat held a firm grip on Tarhuna, wrested violently from its rivals and maintained through occasional purges. Until Haftar’s offensive, its strict rule provided the town with a modicum of stability.

“If you’re in Libya in 2015, you look around and it’s just a nightmare everywhere you look. Tripoli was very dangerous, you had Daesh in Sirte and Daesh in Sabratha, corpses on the beaches of Zuwara, it was just horrible everywhere,” Harchaoui says.

“And Tarhuna was very pleasant. It was quiet, it was very safe – you know, how North Korea is very safe.”

The Kanis bet that backing Haftar would only increase their wealth and status. It was a bet they lost.

‘It could not end well’

By 13 November 2019, things were not going well for Haftar or the Kanis.

Mohsen was dead, Gharyan, the LNA’s other supply line to the Tripoli front, had been retaken by the GNA, and a daring attack on Tarhuna’s al-Dawoon neighbourhood the month before had shown that the Kaniyat were vulnerable.

Disappearances were increasing, so when Ahmed Abdul Moler Saed Abdul Hafid received an anxious call from his brother that evening, he feared the worst.

“The call was short. All he managed to say was ‘I’ve been stopped in my car’ before the line went dead. Immediately I realised the Kanis had him, and knew it would not end well.”

Abdul Hafid, 39, had previous run-ins with the Kanis. Two years earlier they had extorted him and forced him to buy camels at an exorbitant price. But he’d always coped with their demands well. This time he assumed money could get him out of trouble again.

“At around 12am I went to my family home, found the rest of my brothers and told them to gather as much money as they could for ransom.”

From there he went home, turned off all the lights and lay down with his wife, pretending no one was home. After a sleepless night, he heard more chilling news. The rest of his brothers had been taken.

Abdul Hafid knew he had to get out, and with the help of a friend, who would then be seized for assisting him, crept out of Tarhuna and walked 80 km north to the town of Tajoura.

“Everything they did came out of nowhere. You cannot even measure their criminal behaviour, there was no limit,” Abdul Hafid says, sitting bolt upright in his family’s reception room, the memories leaving his face pallid and wrought.

“I lost five brothers to the Kanis, and a friend who was more than a brother,” he says. “There was no obvious reason for their arrest. We are businessmen, not al-Qaeda or the Muslim Brotherhood.”

Like many other Tarhunis forced to flee, Abdul Hafid rushed back to his hometown the day the Kaniyat left. “When I walked through the door of my family’s home my mother fainted, then fainted again. I shouted ‘where are my brothers, where are my brothers?’ I knew something was deeply wrong.”

The prisons were open, but there was no sign of his siblings.

“The Kanis are not people, they are savages. We heard reports people may have been fed to lions.”

***

Daniel Hilton is Middle East Eye’s senior news editor. Previously he was based in Beirut, where he was region editor of Lebanon’s The Daily Star newspaper.

___________