By Florence Gaub

After a decade of violence, Libya appeared to be finally on track for stability. The agreement had only one major flaw: it left any security-related decisions for a later stage.

After a decade of violence, Libya appeared to be finally on track for stability. The agreement had only one major flaw: it left any security-related decisions for a later stage.

2025: THE TIPPING POINT

It was yet another sunny May morning in Tripoli when the EU ambassador was kidnapped.

Her convoy had been on the way to a meeting at the United Nations when a roadside bomb hit the first car. “Exit!” yelled the driver of the ambassador’s car, hitting the accelerator to speed past. But he had to come to a screeching halt that threw the ambassador hard against her seat belt: the road was blocked by several pickups.

The kidnappers had clearly studied the protocol of diplomatic convoys in such situations – they had plenty of opportunity in a Libya embroiled in its third civil war.

In the ensuing firefight, two bodyguards were killed, and the ambassador, who was physically unharmed, was dragged into another vehicle.

What was a dark day for Brussels was just another day in the life of Libya at war: that same day, the Islamic State (IS) attacked an oil pipeline, militias abducted children for ransom, and rockets hit hospitals and schools.

Mercenaries from Sudan and Chad patrolled streets in Benghazi, and Turkish troops were accused of war crimes in Tripoli. Libya’s third civil war was nearing the end of its second year, and no resolution appeared in sight.

“Where did this all go wrong?” the ambassador reflected as she crouched handcuffed and blindfolded in the kidnappers’ car. When she had taken up the post in 2023 Libya had just been through two comparatively stable years.

But now, war was in full swing, with new levels of violence and destruction on a daily basis. “Please God, let this not be the Islamic State” she prayed.

2021-2025: INACTION

All had looked rather hopeful back in 2021. The arrival of Jan Kubis, the new head of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), had paved the way for the most successful peace process yet.

Channelling the spirit of the defunct Jamahiriya, Kubis had called for a People’s Congress, bringing together the representatives of the Tobruk-based House of Representatives along with the High Council of State, adding the representatives that had been elected at municipal level since 2014.

The Congress agreed to the creation of a federal system inspired by Libya’s first political structure following independence, and created two chambers that would effectively be filled with members of the Tobruk and Tripoli parliaments.

The agreement was bolstered by a ceasefire in place since early 2021. The ceasefire was to be monitored by an international military observer mission of 5,000 troops, including EU member states, but also Russian and Turkish troops.

After a decade of violence, Libya appeared to be finally on track for stability. The agreement had only one major flaw: it left any security-related decisions for a later stage.

Armed groups were to continue to be in charge of security in their respective localities, with the High Security Council, made up of representatives of these groups, meeting every other week to exchange information and coordinate.

For the time being, it was considered to be enough to try and stabilise the security situation in Libya. There was indeed a logic to postponing the difficult discussions on the security sector: it was one of the main areas in which lack of agreement had obstructed previous attempts at peace.

Neither the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement, nor the 2020 Libyan Political Dialogue Forum had included thorough and detailed ideas on the future of the security sector. Once a commonly accepted political structure was in place, so the reasoning went, this would create conditions for the more difficult discussions.

This ignored one of the main tenets of successful Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR): that it has to be a continuous process flanking any political undertaking, rather than a separate sequence of events.

It also meant missing the window of opportunity the agreement itself had created: the enthusiasm and support from various actors could have been seized to push through on the most sensitive issue. And security was a highly difficult domain in Libya: not just the political ambitions of militia leaders made it a complicated area to touch.

250,000 or so men were under arms, organised in several hundred militias of varying sizes, equipment levels and influence. Even though most of the 15,000 mercenaries from Syria, Chad and Sudan were in the process of leaving Libya, several other foreign actors stayed behind – notably the IS in Libya’s South.

In addition, the country was awash with weapons – after the war in 2011, it was estimated that 15 million light weapons had flooded Libya’s black market from looted stockpile and weapons deliveries.

In the years thereafter, the UN arms embargo was ineffective, and armoured vehicles, armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), combat helicopters and combat aircraft were delivered by Russia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

But following the establishment of the People’s Congress, the security situation remained calm, and DDR was not a priority.

The ceasefire allowed for oil production and reconstruction; the new political arrangements allowed for some level of dialogue; and the small peace-keeping mission (tasked with managing the demilitarised zone) seemed to ensure a degree of compliance with the agreement.

But by 2022, old conflict lines reappeared, at first in the oil sector. Disagreements over resource allocation and salaries showed that Libya’s economy, too, was in dire need of reform.

From there, it quickly spiralled into a heated debate over Libya’s political structure and power. By 2023, the kidnapping and subsequent assassination of the oil minister led to the mobilisation of several militias. The international mission had neither the mandate, nor the firepower, to stand in their way.

BEYOND 2025: THE COSTS OF INACTION

Once fighting had resumed, the political structure created to prevent it collapsed quickly. European troops withdrew from Libya not much later after a terrorist attack killed 12 Belgian soldiers.

These developments also led to the release of the EU’s ambassador. She was not the only one who had become a pawn in Libya’s escalation game: Russian soldiers were discovered beheaded in Eastern Libya, and a Turkish frigate sank in the harbour of Misrata following a terrorist attack.

Fighting between militias was concentrated along the coast, but in the south, the IS had established a firm presence. It had now doubled in strength as foreign fighters joined its ranks from Tunisia and Egypt, and expanded operations south of the Sahel zone.

This was also the most violent of Libya’s three civil wars: with more than 21,000 people killed in 2011 alone, and 22,000 between 2014 and 2020, the death toll now approached 200,000.

By 2027, over a million people had fled Libya as the war made conditions unendurable for the population.

After three years of fighting, Libya’s civil war finally came to an end with the revival of the People’s Congress in 2028. This time, a large-scale DDR programme was included in the negotiations leading to the ceasefire, and Libya invited a UN mission to supervise and enforce the process.

Economic reforms flanked the process, facilitating the integration of the 250,000 or so men under arms. Under the supervision of a much stronger UN blue helmet mission, Libya’s security sector was finally beginning to be rebuilt from scratch.

In a much-watched ceremony broadcast on national TV, 300,000 weapons were destroyed on Martyr’s Square in Tripoli – of course, these were just the tip of the weapons iceberg.

In 2035, this process was finally declared completed. The EU ambassador who had been kidnapped in 2025 was invited to attend the ceremony.

In her remarks, she stressed that “nowhere is the cost of international community inaction clearer than in Libya. But while outsiders made the mistakes, Libya paid the price.”

***

TIMELINE

- COST OF INACTION: Civil war lasts until 2028. Then, another attempt at peace including security provisions proves to be lasting.

- TIPPING POINT: Conflict in Libya erupts again, facilitated by presence of weapons and militias that never disbanded.

- INACTION: Peace Agreement includes no clauses pertaining to DDR Weapons continue to circulate unchecked, while militias act with impunity.

Heavy Machinery

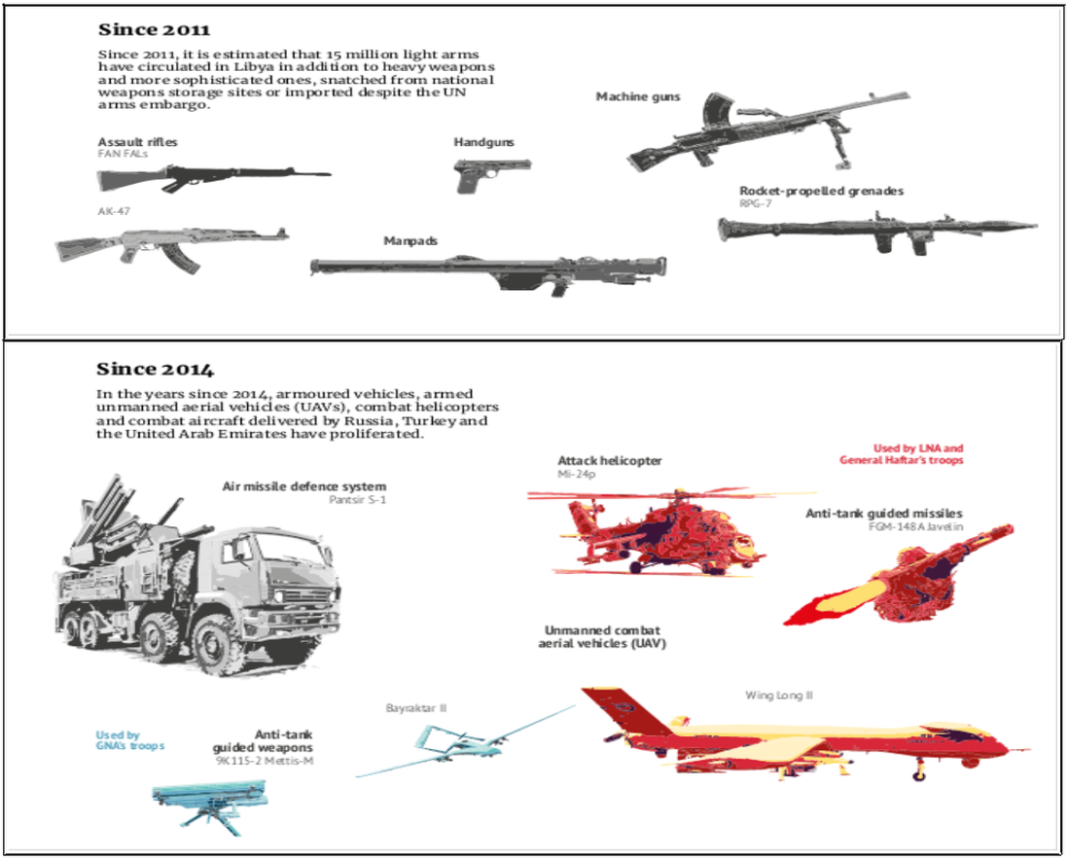

Weapons spotted spotted in Libya since 2011

Since 2011

Since 2011, it is estimated that 15 million light arms have circulated in Libya in addition to heavy weapons and more sophisticated ones, snatched from national weapons storage sites or imported despite the UN arms embargo.

- Assault rifles .. FAN FALs

- Machine guns

- Handguns

- Rocket-propelled grenades

- RPG-7

- AK-47

- Manpads

Since 2014

In the years since 2014, armoured vehicles, armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), combat helicopters and combat aircraft delivered by Russia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates have proliferated.

Used by LNA and General Haftar’s troops

- Attack helicopter – Mi-24p

- Air missile defence system – Pantsir S-1

- Anti-tank guided missiles – FGM-148A Javelin

- Unmanned combat – aerial vehicles (UAV)

- Wing Long II

Used by GNA’s troops

- Bayraktar II

- Anti-tank guided weapons – 9K115-2 Mettis-M

***

Data:

- Final reports of the Panel of Experts concerning Libya 2012-2015

- Final reports of the Panel of Experts concerning Libya 2015-2019

____________

Source: Chapter 11 ‘in WHAT IF … NOT? The cost of inaction’ Edited by Florence Gaub. CHAILLOT PAPER /163. January 2021

European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)