Between people power and state power

By Frederic Volpia & Ewan Stein

This paper examines the trajectories of different Islamist trends in the light of the Arab uprisings. In the following section, we track the evolution of statist and non-statist Islamist activism in the region in light of changing state dynamics.

This paper examines the trajectories of different Islamist trends in the light of the Arab uprisings. In the following section, we track the evolution of statist and non-statist Islamist activism in the region in light of changing state dynamics.

PART THREE

4. Islamism following regime change: explaining differential outcomes

In seeking to understand Islamism’s ongoing relationship with the state, it is important not to focus solely on the impact of “regime change” (or failure, or resilience).

Beyond the immediate significance of regime change or revolutions, the uprisings opened up new possibilities in the general evolution of the state structure and mode of governance across the region.

It is more useful to view the transformations in countries like Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Yemen – as well as Syria, Iraq, Morocco and other countries where regimes remained in place – as part of a continuum of political change that impacted the short- and medium-term prospects of Islamism.

4.1. Statist Islam and the uprisings

Statist Islamism can, generally speaking, claim credit for the expansion of the political sphere in the Arab world, as a potential driver of democratization.

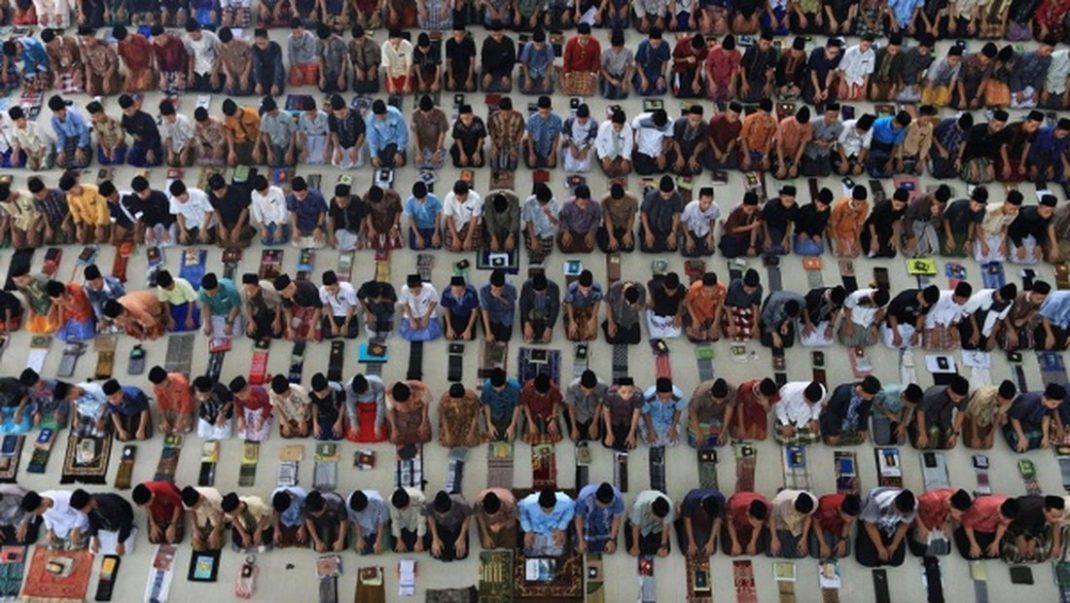

In some cases, Islamists showed themselves to be highly adept at building structures of mass inclusion in authoritarian settings in which elite circulation was absent (Egypt).

In others, this political effort could only take place after the fall of authoritarianism (Tunisia). The uprisings of 2011 directly challenged the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes. They also challenged statist Islamism.

They were able to mobilize significant numbers of people around slogans not related to religion or identity, something that struck at the heart of the “culture wars” framework that had served to

neutralize dissent for decades. Hopes were high that societal unity would carry the day.

In mobilizing on political and economic issues directly (bread, justice, freedom) protesters challenged all parties, but especially Islamists, to explicitly link their culture and identity claims to concrete plans for political and economic renewal.

While statist Islamists can build political parties with substantial popular appeal, these dynamics are only supportive of democratization processes when they become institutionalized.

Beyond the revolutionary moment of 2011 the challenge for the countries of the Arab uprisings is to institutionalize both the increased level of elites’ circulation and the increased level of mass inclusion resulting from the revolution in order to make them sustainable in the longer term.

What the experiences of the Arab uprisings illustrate is that outcomes were as much the result of the choices made during and in the aftermath of the uprisings as they were of longer term path dependencies.

Islamists faced key challenges in using the new opportunities to establish their presence in the post-uprisings political space.

First, statist Islamism was diversifying, and particularly in Egypt the Muslim Brotherhood no longer had the political field to itself.

Due in part to the process of estrangement that had taken place within the Islamist firmament from the 1980s, however, the new engagement did not take place in a way that coherently linked statist and grassroots challenges together.

What has been termed “political” or “democratic” salafism, as embodied by Egypt’s Nour Party, was shunned by many within the broader salafi sphere.

This contributed to the intra-salafi fracturing that became apparent following the ouster of President Morsi into those in the statist sphere that continued to support Morsi as a legitimate leader and those that endorsed the military takeover (or who chose to leave the national politics once more).

Secondly, Islamists also struggled to win the support of protest movements that saw them as “hijackers” of the revolutions – a factor encouraged both by the evident deal-making that was occurring between the old regimes and Islamists (particularly in Egypt and Yemen) as well as by many Islamists’ “accommodationist” track records.

The longstanding antipathy between Islamist and secular actors (part of authoritarian divide and rule strategies) outlasted the overthrow of dictators.

At the same time, statist Islamists struggled to consolidate and expand grassroots support for a political path fraught with compromises that seemed to fly in the face of long-cherished Islamist values.

The contrasts between Egypt and Tunisia illustrate some of the principal factors that determined whether statist Islamists could effectively use the opportunity provided by the uprisings.

4.1.1. Egypt

While the fall of the Mubarak regime opened the door to a reconfigured political sphere, the political class as a whole (Islamist and non-Islamist) failed in the crucial transition period – due to a range of domestic and international factors – to realize a constitutional framework that would guarantee elite circulation.

The Egyptian case is indicative of the vicious circle that a struggle for power at the top of the state, and legacies of authoritarian rule that precluded cooperation in civil society, can create.

The actions of the statist Islamists (especially Muslim Brotherhood), of the military institution and of the elites from the former regime (particularly in the judiciary) prevented the routinization of multiparty and electoral politics.

For one, the contending political actors failed sufficiently to bridge the numerous divides that had segmented Egyptian politics over the previous decades.

Even though the Muslim Brotherhood commanded a substantial following, as evidenced by the electoral performance of its political offshoot, the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) and Morsi’s (albeit narrow) victory, it failed to translate this support into deal- making on a constitutional framework.

On the one hand, owing to legacies of mistrust from the Mubarak period, the Brotherhood and most other Islamist forces were unable to sustain an alliance with secular political parties or the revolutionary youth.

On the other hand, despite early attempts to demonstrate its willingness to work with the existing coercive structures of the state (as represented by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces), the Brotherhood failed to convince the military and security apparatus that it was a reliable political partner.

The inability of the contending political forces to find mutually acceptable “rules of the game” meant that growing popular opposition to Brotherhood rule did not spur further democratization and was instead directed toward the “exceptional” measure of a military coup in the absence of working institutionalized processes to mediate between contending interests.

The high level of mass inclusion that occurred during the uprisings was then temporarily institutionalized via a “neo-populism” centring on the personality cult of Abd al-Fatah al-Sisi and the prestige of the military, rather than being linked to the principle of a rotation of elites.

The resurgent military regime in Egypt has destroyed the Muslim Brotherhood’s ability to connect with its constituencies and hence function as a vehicle for inclusion – even a parallel one – as it had in the past.

The Brotherhood has weathered repression from the regime before, but as Saad Eddine Ibrahim recently pointed out, the 30 June “Revolution” that precipitated a military coup four days later was the first time the Brotherhood had faced a mass popular rebellion.

The sheer scale of this uprising, exaggerated as it may have been, seriously damaged the Brotherhood’s image as a popular movement in the region and hence as a conduit for democratization.

The new Sisi regime in Egypt has its founding solidly grounded in a myth of popular sovereignty represented by the popular uprising of 30 June.

Large numbers of secular intellectuals support the eradication of the Muslim Brotherhood even if they do not support the retrenchment of military-led authoritarianism in Egypt.

In this respect, the Egyptian trajectory can be presented as a case of tentative return to the old culture wars encouraged by the new military regime.

Islamists were not mainstreamed as conservative parties in an institutional framework that guaranteed a regular rotation of political elites and Islamism’s capacity to act as a vehicle for mass inclusion was so undermined that even if some form of elite circulation is established it will likely assume a “decorative” form (façade democracy, pseudo-democracy), lacking a meaningful democratic connection with the electorate.

The potential of the Muslim Brotherhood and political Salafis to become handmaidens of democratization was lost.

4.1.2. Tunisia

A democratizing Arab state can be seen as a direct institutional outcome of the 2011 Arab uprisings in only one case, that of Tunisia.

Rather than facilitating a return to authoritarian rule (either directly by taking advantage of their political success or indirectly by inciting their opponents to grab power for themselves) or undermining the capabilities of the state institutions, the Islamists of Ennahda contributed to the stability of the post-revolutionary democratic institutions and practices.

The normalization of statist Islamism is tightly imbricated into the process of consolidation of multiparty democracy in the country.

As significant as the actual revolutionary uprising and foundational elections of 2011 were the processes of democratic consolidation that occurred subsequently (or in parallel).

In this period the Islamists of Ennahda governed in coalition with leftist parties, and struck deals over the constitution and the holding of new elections with the main secularist forces of the country.

Ennahda chose to tone down Islamist ideological claims and appeal to middle class voters via their general conservative outlook and “good governance” programme.

This downgrading of the ideological claims of statist Islamism in a “democratizing” institutional context is best illustrated by the agreement reached on the new constitution with secularized parties, which resulted in the absence of direct references to the sharia in the text of the constitution.

By making concessions on the constitutional framework and on their utilization of executive power, Ennahda facilitated the acceptance by social and political actors across pre-existing ideological divides of a democratic model in which most political parties estimate that losses today can be compensated by gains in the future.

The mainstreaming of Ennahda is also exemplified by the decision of the Ennahda-led government to hand over executive power to a technocratic government that was more acceptable to the opposition a year ahead of planned parliamentary and presidential elections.

In the 2014 parliamentary elections, Ennahda came in second position, thus illustrating the “normality” of an institutionalized Islamist party in a functioning multiparty democracy characterized by a rotation of elites.

Rather than seeking to have an immediate impact on the state institutions and state governance, statist Islamists in Tunisia have prioritized becoming an entrenched, mainstream party with a say in public and political life regardless of whether they are in opposition or in government.

From an agent-centric perspective, it could thus be said that the strategies of the key actors of the Tunisian transition were conducive to a consolidation of democracy.

But for Ennahda and its secular rivals to deepen their support bases and ward off the threat of “culture wars”, the daunting task of narrowing socio-economic inequalities must be tackled.

In such a case, statist Islamists move from purely cultural and moral claims as their main source of legitimation and become a party grounded on socioeconomic policies that are drafted to appeal to a non-ideologically defined electorate.

…

to be continued

***

Frédéric Volpi is Deputy Director of the Institute of Middle East and Central Asia Studies and Senior Lecturer in International Relations at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of a number of books on political Islam and democracy in the Muslim world, and is coordinator of the BRISMES research network.

Ewan Stein – Senior Lecturer in International Relations. His research interests include the international relations of the Middle East, particularly the role of ideology and intellectual dynamics, political Islam, and the politics and foreign policy of Egypt.

____________

University of Edinburgh