By Lorenzo Marinone

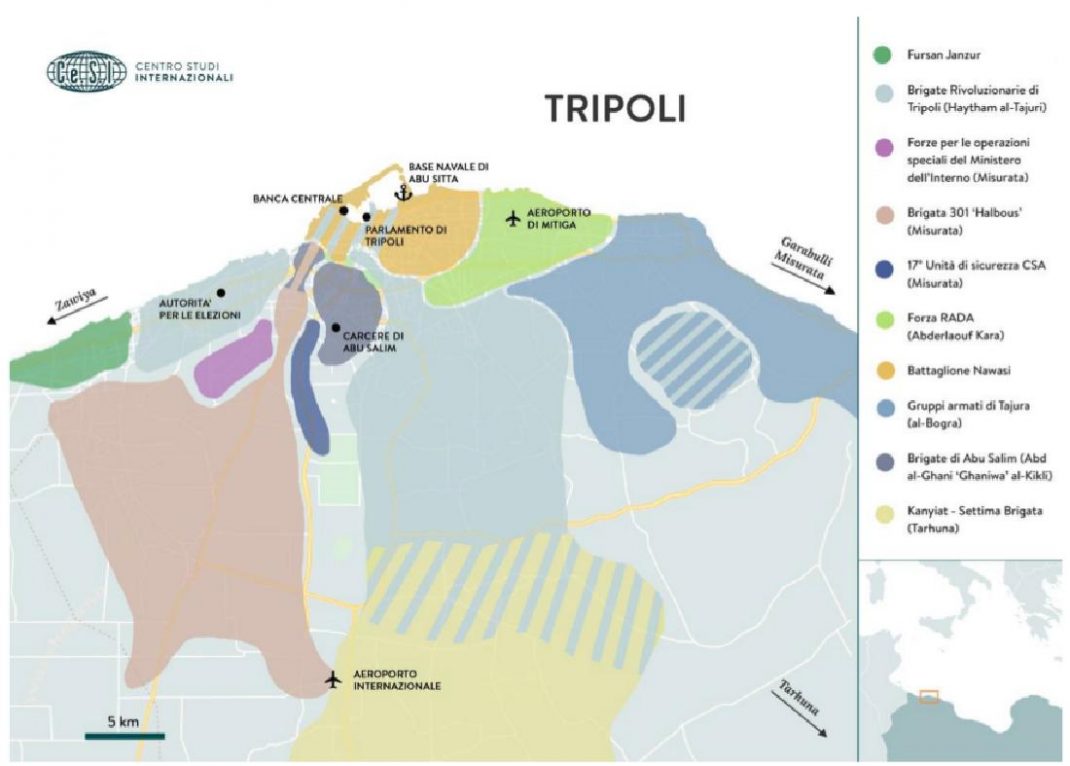

Since August 26, Tripoli has witnessed violent clashes between rival militias until UN brokered a fragile ceasefire on September 4.

PART TWO

In brief, a volatile security framework in Tripoli acts as a real bottleneck that undermines efforts of political and economic reconciliation.

Against this background, it is quite clear that the acceleration impressed by the French diplomatic initiative, with the Paris summit on May 29, contributed to destabilizing the situation in Tripoli.

As mentioned earlier, the conference brought together a small number of actors (Serraj, Haftar, the President of Tripoli’s High Council of State, Khaled Mishri, and his counterpart in the Parliament of Tobruk, Aguila Saleh), who agreed on a short timeline to hold elections by the end of 2018.

Inevitably, the simple fact of holding elections would result in a new landscape of actors legitimated by the international community. However, it is precisely the quest for a form of legitimation (and the attempt to prevent rivals from obtaining it) the main cause of conflict in a country that still has multiple poles of sovereignty, such as Libya.

The rush to the polls, therefore, risks turning out to be an ill-advised stretch, with the potential to reproduce the same post-elections scenario as in 2014, when the outcome was not recognized by the defeated parties.

This eventuality is made even more concrete by the ambiguity surrounding some legal aspects of the path that would lead to the polls.

The Paris summit stipulated that the provisional Constitution, drafted in 2017 by a devoted assembly, named Constitution Drafting Assembly (CDA), and possible legal basis of the vote, will be approved through a referendum.

CDA then requested the Parliament of Tobruk to promulgate a law that regulates this public consultation. In theory, the referendum should be held by September 16, but Tobruk has yet to pass the law because it repeatedly failed to reach the needed quorum. On this legal basis the parliamentary and presidential elections would then be called for December 10.

A first potential obstacle emerges here, since the Parliament of Tripoli has not been directly involved and could contest the validity of the procedure followed so far, as well as a referendum law approved by an assembly, Tobruk’s, that Tripoli deems without any legitimacy.

However, a substantial part of the Parliament of Tobruk is clearly dissatisfied with the new Constitution, despite being the outcome of a transversal body such as the CDA, created in February 2014 and composed of 60 members, equally originating from the three historical regions of Libya.

In fact, it bans dual nationals from political roles, and it confers the role of Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces to the President.

These provisions actually exclude Haftar, who has Libyan and US passports, both from the presidential race and from the top of military apparatus, thus condemning the General to a subordinate position in the future Libyan state.

So, in order to fix the Constitution before elections, Tobruk appears to have deliberately drafted the referendum law in such a way as to assign a veto power to the electoral district of Cyrenaica (where, presumably, Haftar has the ability to influence the vote).

Thus, if the referendum fails, according to article 8 of this law, it would be up to Tobruk, and not the CDA, to draft a new Constitution. This new Chart would likely closely reflect Haftar’s aims, but it also risks being rejected by the General’s staunchest rivals.

Furthermore, the President of the Parliament of Tobruk Saleh has threatened to bypass the referendum on the new Constitution, and then to resort to the law No. 5 of 2014, which in his view would allow him to call for elections for a temporary President without the approval of the legislative bodies and, above all, without the restrictions that at the moment ban Haftar from the political arena.

Obviously, this path would be absolutely unacceptable for Tripoli. In any case, a prolonged impasse would further erode mutual trust between Tripoli and Tobruk, and risks exacerbating frictions.

In particular, the ongoing disputes concerning the control of crucial institutions for Libya’s oil-rentier economy, such as the National Oil Company (NOC), the Libyan Central Bank (CBL) and the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA).

The authorities of Cyrenaica have already created a parallel NOC and CBL and rekindled the threat of secession, even if these institutions did not get international recognition. So far, the dispute has therefore been limited to calls for a reshuffle of top managers (the Cyrenaica authorities have long called for the removal of Sadiq al-Kebir, head of CBL in Tripoli), or for greater transparency.

However, Haftar has already demonstrated that he is willing to use his position of strength in the Oil Crescent to fuel Cyrenaica’s autonomist and separatist tendencies, and to add pressure to the Government of National Accord.

In fact, last June, after repelling an offensive in the Oil Crescent by militiamen loyal to the former head of the Petroleum Facilities Guard, Ibrahim Jadhran, the General briefly put the management of the hydrocarbon plants in the Gulf of Sirte under the “separatist” NOC in Benghazi, and blocked exports from Zueitina and Hariga terminals for a few days.

In this context, where local actors struggle to converge towards a shared approach to shape the future structure of the country, the absence of a cooperative logic in how the International Community acts undermines its crucial support to the UN-led reconciliation process.

Against this background, Italy can contribute concretely to tempering tensions. In fact, Rome maintains open channels of dialogue with a wide range of local actors. In addition to the support granted to Serraj’s GNA, discreet contacts with the authorities of Cyrenaica and Haftar have never ceased.

Moreover, since 2011 Italy has cultivated relations with Misrata, not least launching Operation “Ippocrate” in September 2016.

Regardless of potential changes in Tripoli militias landscape, recent clashes could provide an opportunity to both reaffirm GNA as a key institution in the national reconciliation process, and make it more inclusive and representative via a consultation with Tripolitania’s marginalised players and Eastern actors.

In this sense, Italy could mediate and support that replacement of GNA leaders requested by many local players and hinted at by UN Special Envoy for Libya Ghassam Salamé.

To this end, the relationship between Rome and Misrata could play a central role. In fact, the prolonged political impasse pushed many in Misrata’s civil and military institutions to take on a neutral stance regarding the conflict between Tripoli and Tobruk.

In this sense, it was emblematic Misrata’s open dialogue with Cyrenaica military leaders launched in 2017 and mediated by Egypt, with the aim of laying the foundations for a reunification of Libyan Armed Forces.

In light of these contacts, Rome’s room for maneuver in the reconciliation process could widen if the recent Italian attempts at rapprochement with Egypt, a traditional supporter of Haftar, were

successful. So, at this stage, Rome can exploit a valuable window of opportunity to underline shared concerns, from regional security to the urgency of preventing a new phase of chaos in Libya that could provide fertile ground for a growth of jihadist organizations.

Although the resumption of this dialogue may irritate France, hitherto relying on the axis with Egypt, it is quite clear that no lasting political solution for Libya can be put in place effectively without the consent of a regional actor as important as Egypt.

On the other hand, Rome seems willing to adopt a markedly inclusive approach in dealing with the Libyan dossier. In fact, the format envisaged for the Italian conference on Libya scheduled for next November, includes the Arab League, China and the United States.

This initiative could be perceived by Paris as an attempt to dilute its weight in determining the future of Libya, and therefore is exposed to the risk of fueling an Italian-French rivalry that has already grown significantly in recent months.

This could consolidate one of the main hindrances in the reconciliation process, that is the tendency of each country to support certain factions, also and above all to safeguard specific national interests in Libya.

So far, these national interests resulted into supporting certain actors partly in light of their geographical location.

Consequently, in order to gain greater overall stability of the country, any negotiation process cannot ignore the specificities and demands of each Libyan region.

In this sense, it is crucial to delineate an institutional architecture that, while being adequately representative of Libyan regionalisms, is to be based on a unitary framework that would allow any local actor to have a voice in crucial decisions such as the management and redistribution of oil&gas revenues.

***

Lorenzo Marinone – Analyst for Middle East & North Africa affairs of Ce.S.I. – Centro Studi Internazionali. – Centre for International Studies. He holds a Masters in Peacekeeping and Security Studies earned at the University of Roma Tre in 2014. He has been frequently interviewed as commentator on national TV and radio broadcasts.

***

The Source: REPORT: THE LIBYAN MAZE. THE PATH TO ELECTIONS AND THE FUTURE OF THE RECONCILIATION PROCESS . Edited by Lorenzo Marinone

__________________