By Al-Hamzeh Al-Shadeedi & Nancy Ezzeddine

This policy brief will provide recommendations on how to realistically and effectively engage with tribal actors and traditional authorities for the benefit of the current central state-building process, while avoiding past mistakes.

This policy brief will provide recommendations on how to realistically and effectively engage with tribal actors and traditional authorities for the benefit of the current central state-building process, while avoiding past mistakes.

PART ONE

National politicians and international actors cannot ignore the resilience of premodern tribalism in Libya.

Libyan governance structures have historically relied on the top-down distribution of favours to selected tribal allies, rather than on inclusive and representative governance.

Such arrangements took the shape of cyclical processes of selective co-optation, exclusion, rebellion and, again, new forms of selective co-optation. Even the uprisings of 2011, which symbolise the appearance of a national Libyan polity, was mobilised and organised along tribal lines.

Accordingly, efforts to build a new Libyan state today should take into account the strong tribal character of Libya and should look into integrating tribal forces into the state in a manner that favours the central state project while simultaneously allowing for true representation and inclusion of all local and tribal entities.

This policy brief will provide recommendations on how to realistically and effectively engage with tribal actors and traditional authorities for the benefit of the current central state-building process, while avoiding past mistakes.

Introduction

The tribes of Libya are considered one of the country’s oldest, longstanding societal institutions. The country has historically witnessed the entanglement of tribes and politics, a dynamic that continues – and arguably may have become more prominent – in post-Gaddafi Libya.

At present, Libyan institutions mainly advance individual and city interests rather than the public good, and attempts to re-establish stable central control over these government structures have so far failed.

In this context of government ineffectiveness or absence, tribes have become more prominent and in some areas even more powerful than formal actors.

The international community and foreign analysts have watched this development with suspicion, as they fear that further fragmentation of power and governance along tribal lines could contribute to the prolongation of chaos and conflict.

However, approaching the situation in Libya from such an angle risks losing focus on other aspects of the conflict. Libya’s civil war and current fragility is not caused solely by its tribal tendencies. Tribal mediation, conflict resolution, and reconciliation mechanisms might be beneficial to the process of bringing about peace and political stability in Libya.

For example, in the post-2011 turmoil, the tribes’ method of resolving conflicts in Libya, known as Urf, has expanded into an established judicial system to fill the void left by the state and to face the realities of civil war.

Furthermore, according to many respondents in a recent Clingendael-led survey on local security provision in Libya, tribes offer the only functioning judicial system in Libya and are therefore seen as legitimate governance actors.

This fits within a historical dynamic in which tribes and tribal identity have become stronger whenever the state faced a crisis and when state institutions failed to carry out their responsibilities and meet people’s expectations.

Moroever, when central government is unable to control its territory, tribes take over responsibilities that the state should assume, such as the provision of justice and security. This begs the question what role the international community and future Libyan governments should envisage for tribes in Libya’s future political settlement?

This brief’s historical overview of the role of tribes in Libya’s political life shows that tribal empowerment through political means – for example, by endorsing the role of tribal authorities in (local) governance – can have negative consequences down the line.

Libya’s modern history is filled with examples where the entanglement of tribes and politics has thwarted the creation of credible state institutions.

The clan based logic of tribes, moreover, invites the development of patronage systems that benefit some sections of the population but not the country as a whole. Yet tribalism should be factored into efforts at improving local and central governance – particularly because the results of previous attempts to marginalise or circumvent tribal systems in Libya’s state formation process range from inefficient to destructive.

The tribe and state in Libya: a historically strained relationship

The tribe (qabila) in Libya should not be understood as an ancient and static social structure but rather as an everchanging entity which can include a wide range of social organisations.

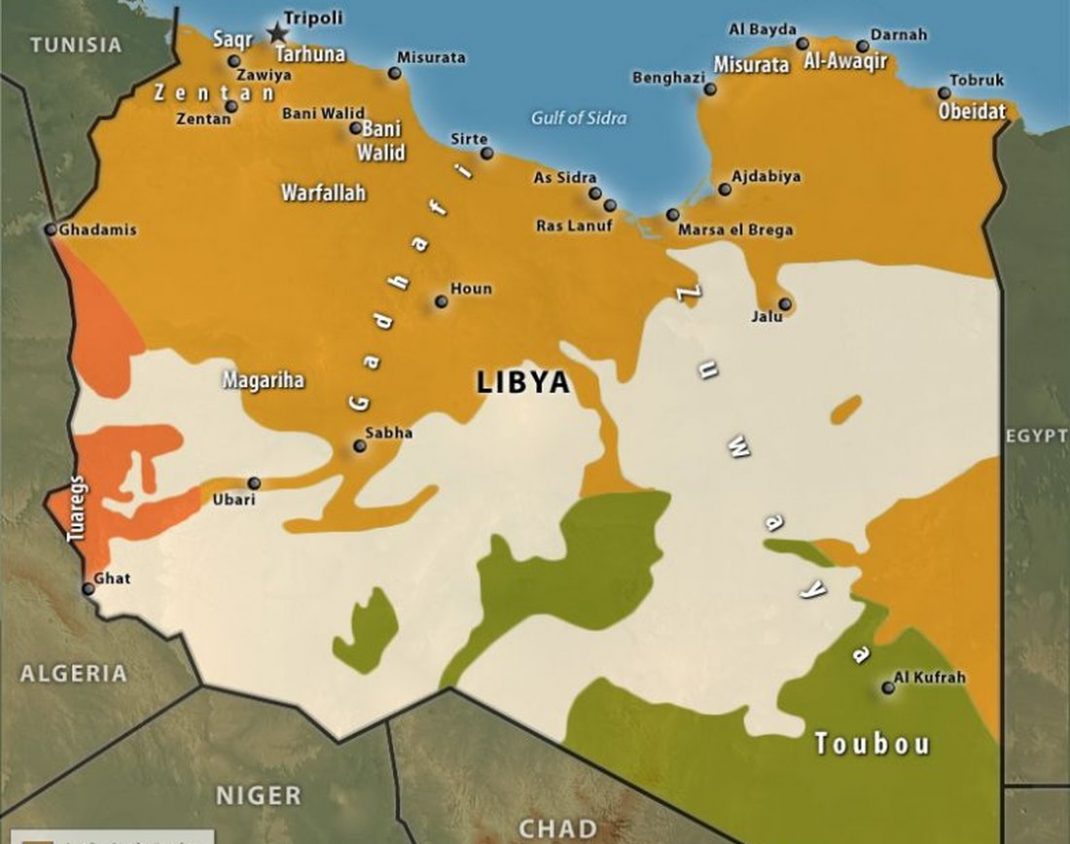

There are over a hundred tribes in the country, with 30 key players.

The majority (90%) of Libyans are a mix of Arab or ethnic Arabs and Berber. The nomadic Tuareg, the Tubus in the south and the Amazighs are minority tribes.

At present, around 90 percent of the total population is linked to a tribe, while only 10 percent are not tied organically to any tribe, notably in the northern Libyan cities. The two most important Arab tribes and the most influential come from the Arabic peninsula, these are:

– the Beni Salim tribe, which installed itself in Cyrenaica and on the eastern coastal region of Libya, and

– the Beni Hilal tribe, which historically occupied the western region around Tripoli.

The Amazigh are estimated at 200,000 members and they mostly inhabit the mountains of Djebel Nefoussa and the coastal town of Zuwara.

Given their prominence among the Libyan population, tribes have been both a central element of, and an obstacle to, the Libyan state formation process.

The Ottomans (1551–1912) were the first to institutionalise and formalise tribe-state relations in Libya. The Ottoman rulers depended on important tribal leaders in peripheral and rural areas to collect taxes, levy troops, and control and secure trade routes.

Additionally, the Ottoman authorities stationed in Libya integrated a certain number of tribal elites into the administrative structures of the state in order to implement the authorities’ policies across Libya.

This policy of favouritism allowed for a group of local tribal figures to rise and emerge as new political and economic elites in their localities.

They made use of this new arrangement by expanding their patronage base, influence and wealth. Ottoman administrators allowed this accumulation of power to continue as long as the tribal elites remained loyal to the Sultan in Istanbul and were able to collect and deliver taxes in a timely and peaceful manner.

Ottoman efforts at centralisation and modernisation during the second half of the 19th century, famously known as the Tanziymat, attempted to centralise power in the hands of the Sultan and his government in Istanbul.

The new generation of young politicians who had studied in, and returned from, Europe wanted the Ottoman empire to resemble the new nation states that had emerged in Europe.

Local and tribal actors in Libya and other parts of the empire, were seen as a threat to this objective. Thus, new strategies were developed that aimed to alter tribal control over politics in Libya.

…

to continue in part 2

***

Al-Hamzeh Al-Shadeedi is a research assistant at the Conflict Research Unit of the Clingendael Institute. In this capacity, he focuses on local governance and security settlements in Libya. In addition, he is interested in security dynamics, political settlements, and culture in Libya, Iraq, and the Kurdistan Region.

Nancy Ezzeddine is research assistant at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit. In this role she primarily contributes to the Levant research programme, seeking to identify the origins and functions of hybrid security arrangements and their influence on state performance and development.

___________

CRU Policy Brief