By Sami Hamdi

Despite historically taking a non-interventionist stance, Algeria’s recent efforts to seize the reigns politically in the Libya conflict suggest its foreign policy strategy may be changing.

Despite historically taking a non-interventionist stance, Algeria’s recent efforts to seize the reigns politically in the Libya conflict suggest its foreign policy strategy may be changing.

Despite a flurry of activity following Turkey’s announcement that it would intervene in Libya, which culminated in the much-anticipated January 19 Berlin Conference on Libya, not much has happened since.

The reason for the lull in diplomatic activity is Algeria’s intent to seize the reins politically in guiding Libya out of its current quagmire.

Even with much lobbying from their Turkish counterparts, Algeria has stubbornly denied providing logistical assistance to Turkey. Various statements from all levels of government have insisted that Algeria rejects all foreign interference in Libya, including Turkey’s.

Moreover, Algeria sought out the African Union as part of a wider diplomatic initiative to engage its fellow Africans in bringing Libya out of the European concern into the African realm, where there are fewer personal interests at stake.

Algeria believes that much of Libya’s current instability stems from increasingly competitive European nations jostling for rights to Libya’s resources.

Algeria believes that much of Libya’s current instability stems from increasingly competitive European nations jostling for rights to Libya’s resources.

While Italy believes it should have priority in its old colonial stomping ground, France believes that it deserves to be compensated (and somewhat rewarded) for bringing about the NATO intervention that ousted Muammar Gaddafi.

To this effect, Algeria invited the foreign ministers of Libya’s neighboring countries Chad, Mali, Sudan, Egypt, Tunisia, and Niger in February to discuss the Libya crisis.

The significance of the invitation lies in the fact that each of these countries is directly affected (or involved) in the conflict, but most have been ignored in peace initiatives hosted by European countries.

However, while it is clear that Algeria is pushing for a more united African front and a greater role for the African Union in Libya, the effectiveness of such measures remains questionable.

This is not because the African Union lacks the capabilities or influence to bring about serious negotiations over the future of Libya. Rather, it is in the fact that each of these African nations involved in Libya are not entirely sure what political solution best suits the stability of the region.

The root of this dilemma is in the UAE’s involvement in the country and Libyan warlord Haftar’s intentions. Put simply, Algeria is deeply suspicious of the UAE objectives in the region, which have included interference in elections in Tunisia, deepening ties with rival Morocco, and the exacerbation of tensions across North Africa as a result of Abu Dhabi’s wider war against the Muslim Brotherhood.

In other words, Algeria fears that after Libya, Algeria may well be next. Algeria has no particular affinity for Libyan Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj.

This has been reflected throughout the conflict as Algeria has preferred to avoid providing the necessary backing for Sarraj to effectively push back Haftar in line with its notorious non-interventionist foreign policy.

Nevertheless, Algeria is unsure what solution would bring an end to the conflict and contain UAE expansion and meddling.

Haftar himself is aware of Algeria’s sensitivities. Before his offensive in Tripoli on April 4, 2019, Haftar halted for weeks while monitoring the escalating domestic situation in Algeria, as protests spread across the country against a fifth term for President Abdelaziz Bouteflika in what became known as the Hirak movement.

Only when Algeria became paralyzed by the internal chaos and political infighting that saw the heads of intelligence and security change at least twice, did Haftar launch his full-scale assault in Tripoli.

In other words, Haftar was well aware of Algeria’s aversion to a Haftar-led Libya and feared that if pushed, they would lend their resources and capabilities to Sarraj.

As a result of Haftar’s offensive, Algeria has provided behind-the-scenes assistance to Sarraj to help fend off Haftar’s attack. Whilst this support is lacking on its own, it has proved sufficient when combined with Turkey’s more open support via Bayraktar drones and deployment of mercenary forces in preventing Haftar from seizing the capital.

Algeria has sought to shake Haftar’s backers by inviting Turkish President Recep Erdogan on a state visit in a clear sign that if forced to choose, Algeria would throw its lot behind Libyan Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj.

Furthermore, Algeria has sought to shake Haftar’s backers by inviting President Recep Erdogan on a state visit where President Abdelmadjid Tebboune displayed warm affection for the Turkish President in a clear sign to other states involved in Libya that if forced to choose, Algeria would throw its lot behind Sarraj.

The intended message, that Algeria was ready to intervene and play a role in Libya, was received as the UAE sent its foreign minister to Algiers and Tunis for talks.

Following this diplomatic foray into Libya, Algeria has reined in rumors that it has joined hands with Turkey and since sent delegations to both competing parties in Libya.

Tebboune also met with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi privately at the African Union Summit in early February, demonstrating a clear willingness to engage all parties of the conflict.

Although these movements have at times drawn the ire of both Haftar and Sarraj’s Libyan interim Government of National Accord (GNA), Algeria’s intended message that it is now fully operational and ready to exert itself has been received loud and clear by all parties.

The question remains as to what extent Algeria can influence events in Libya. It is evident from the manner in which international powers have responded to Algeria’s initiatives that President Tebboune commands enough clout to warrant attention and be heard.

However, it has not escaped international observers that while Algeria declares it is non-interventionist, it has privately expressed relief that Turkey stepped-in to halt Haftar’s offensive on Tripoli.

Moreover, Algeria’s attempts to bring in the African Union may well backfire. The UAE now wields considerable influence over Sudan and has steadily sought to win the favor of East African states to cement its ability to influence politics in the Mediterranean.

France also remains firmly behind Haftar and disappointed at the fall of long-time ally AbdelAziz Bouteflika.

Although Algeria’s domestic situation is significantly more stable, it is also still in a process of transition as Hirak protests continue weekly (although with significantly reduced numbers), and debate continues over the timing of expected parliamentary elections.

Algeria’s diplomatic foray offers a new dimension to the Libya conflict and the potential to side-line Europe.

Nevertheless, Algeria’s diplomatic foray offers a new dimension to the Libya conflict and the potential to side-line Europe and bring Libya within the remit of the African Union, Arab League, and neighboring countries.

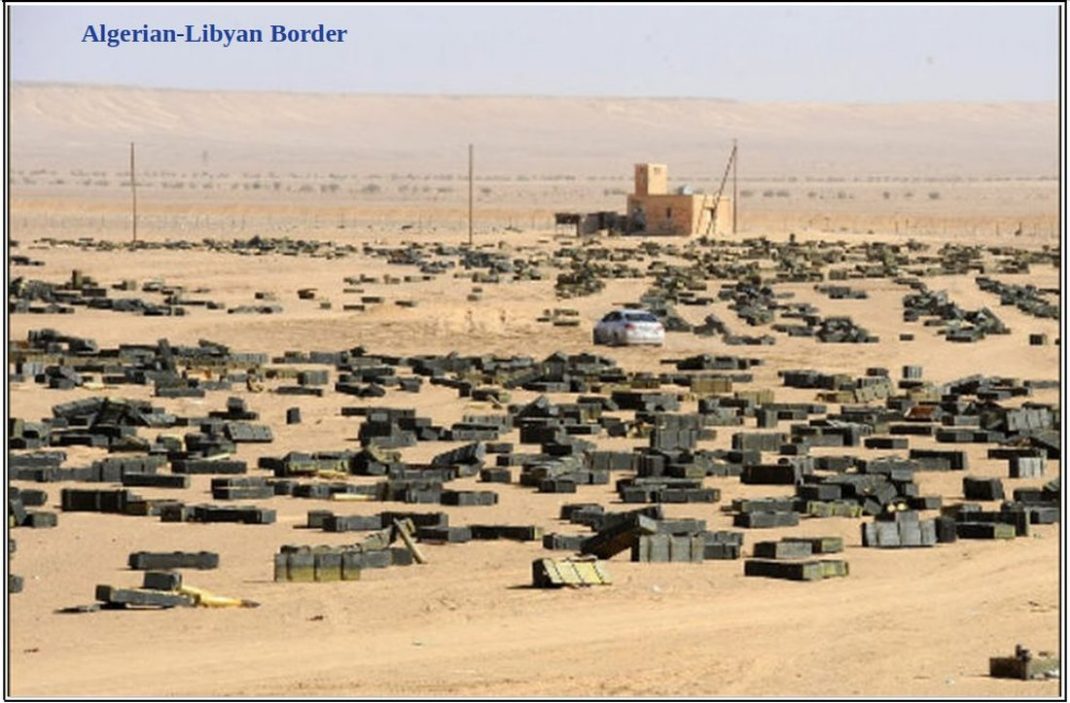

Algeria also retains the capabilities of providing logistical assistance to Sarraj via its long border with Libya in the event Haftar overreaches in his bid to force a military victory.

In other words, Algeria’s emergence from paralysis offers new dynamics both politically and militarily that may well prove conducive in the long-term to a political solution in Libya.

***

Sami Hamdi is the Editor-in-Chief of the International Interest, an experienced foreign policy adviser, and seasoned consultant who has advised governments and global companies on the geopolitical dynamics in the Middle East.

____________