By Mustafa Fetouri

The town of Harawah lies around 80 kilometres east of Sirte and nearly 550 kilometres east of Tripoli. I drove there earlier this month to see the most westerly territory in Libya controlled by the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by former General, now Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar.

The town of Harawah lies around 80 kilometres east of Sirte and nearly 550 kilometres east of Tripoli. I drove there earlier this month to see the most westerly territory in Libya controlled by the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by former General, now Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar.

No one expected Haftar’s self-styled LNA to reach this far into western Libya when he announced his campaign in 2014 to rid Libya of all “terror” groups and bring back security. At that time, Benghazi and Derna in the east were divided between Ansar Al-Sharia, Al-Qaeda, Daesh and a host of other Islamist groups who fought against former leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

After a bloody war, a jubilant Haftar appeared on TV in July 2017 to declare the “liberation” of Benghazi; almost a year later, in June 2018, the LNA took Derna. This made the LNA the dominant force in eastern Libya and Haftar himself an essential part of any settlement in the conflict-ridden country.

Earlier this month, LNA troops were deployed in Fezzan, in the south of Libya, for the first time in seven years. They are attempting to expel armed groups from Chad which are roaming the area, and rein-in quarrelling tribal militias.

On the road from Tripoli I passed through nine checkpoints east of Misrata on the way to Harawah. They are controlled by a Misrata-dominated militia named Al-Bunyan Al-Marsos, the US-backed group that defeated Daesh in Sirte in 2016.

This particular militia remains the strongest anti-Haftar force in western Libya. On paper, Al-Bunyan Al-Marsos is part of the UN-imposed Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli and headed by Fayez Al-Sarraj. The GNA does not recognise Haftar, nor does he accept its legitimacy.

The LNA’s counterattack in 2014 came after activists, politicians, journalists, security professionals and army officers were being assassinated in restive Benghazi on an almost daily basis. Fearing that he might be next, Haftar went on the offensive with around 150 soldiers.

He quickly found backing from Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, who also enlisted support from the UAE. Al-Sisi needed to secure Egypt’s long western border with Libya and Haftar was willing to do that.

The Field Marshal’s relationship with Egypt goes back to the 1973 war against Israel, when he led a Libyan artillery battalion and won a medal of honour.

“Liberating” Libya is not Haftar’s only aim. This is a man who feels that he has a right to lead the country to which he returned during the 2011 civil war after two decades of exile in the US.

He was in America having been taken prisoner in the war in Chad in 1987 and evacuated by the Central Intelligence Agency. He lived a relatively comfortable life in Virginia, not far from the CIA headquarters in Langley.

Haftar joined the Libyan opposition funded by Washington and even participated in the US-supported operation to topple America’s sworn enemy Gaddafi, but the plan failed, like many others before it. Gaddafi remained in power until October 2011 when he was murdered by rebels, some of whom were commanded by Haftar.

The rebels did not really like Haftar, given his role with the group of officers led by Gaddafi which overthrew Libya’s ruling monarchy in 1969.

When the NATO backed 2011 rebellion ended, Haftar found himself rejected by the jihadists who dominated eastern Libya. He was not given any role that he thought he deserved due to his opposition to Gaddafi.

Today, his enemies are defeated while he controls most of Libya; that’s a huge amount of territory.

When I arrived in Harawah, an officer called Hassan Matouk was already leading the LNA brigades streaming into southern Libya in a bid to bring it under Haftar’s control. Matouk was a shrewd appointment by the head of the LNA, because he belongs to the Oulad Suliman tribe in Harawah which also has a sizeable presence in the south.

If anyone could convince the tribe to join the LNA, it would be their own son Hassan Matouk. His priority is to finish the armed Chadian rebels who are roaming the south and then destroy the human trafficking networks before turning to the local tribal militias.

In military terms, the LNA’s presence in the south means cutting any support that the anti-Haftar militias further north are getting and removing the remnants of Daesh who are still active in the desert.

Politically, Khalifa Haftar does not recognise the GNA as a legitimate government and, rightly, believes that it is a militia-dominated administration imposed by the UN. However, he accepts everything else that the UN is proposing, such as elections and pan-Libyan reconciliation conference.

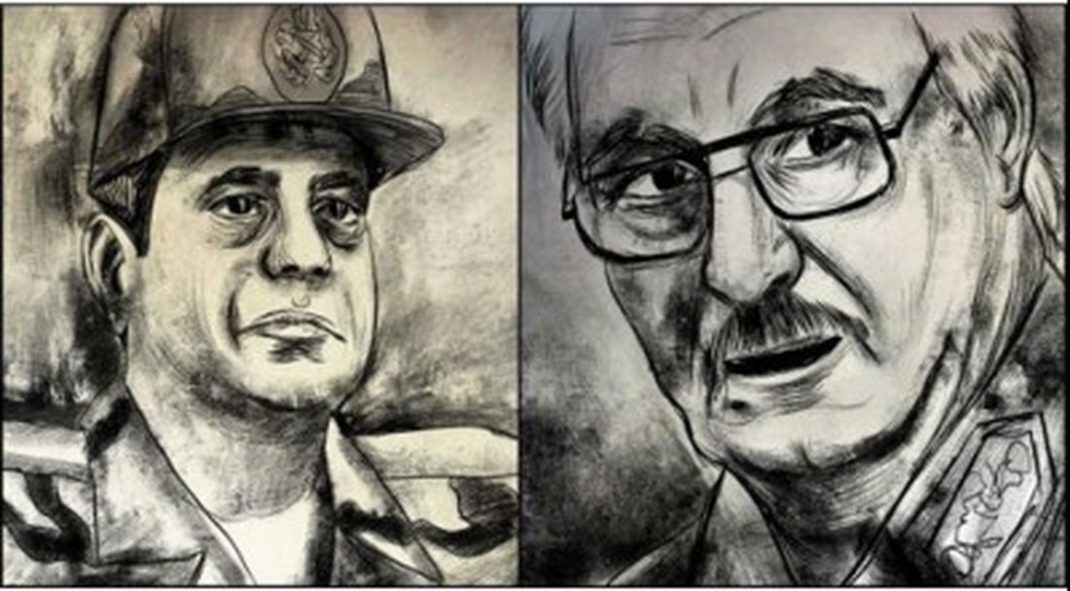

Could Haftar re-model himself on the former General-cum-Field Marshal-cum-President Al-Sisi and take part in elections in Libya? No one really knows, and he has never said anything about it, while insisting that the LNA is an apolitical professional army trying to secure the country. Al-Sisi once said the same thing.

However, Libya is not Egypt and Haftar is not Al-Sisi. The latter led a coup d’état against a democratically-elected government of which he was a member, while Haftar is fighting different groups with no central government to overthrow.

There is also the awkward fact that Haftar has dual US-Libyan citizenship, and Libyan law forbids dual citizens from holding public office, despite the fact that the parliament in eastern Libya appointed him as the commander of the LNA.

What’s more, Haftar has reached retirement age with questionable health, seeking treatment in Paris last April for an undisclosed illness.

No one doubts the Field Marshal’s political ambitions, but could he just be waiting for the right moment to announce them? Is he popular in fractured Libya?

Undoubtedly, he enjoys public support in eastern Libya where he is looked upon as a saviour after bringing security to the region and helping to establish government services in many areas. He is credited with ridding Benghazi of all terrorist groups.

In western Libya, it is a different story. While precise figures are unavailable, Haftar has sizeable public support and many people want him to repeat his Benghazi success in Tripoli. However, those willing to fight against him are easily identifiable but those willing to give him their votes are not so obvious.

Nevertheless, his success in Benghazi and Derna has also made him a figure to look to for leadership and stability in western Libya.

The latest LNA advance in southern Libya is a great victory and provides massive reassurance that Haftar can deliver security and stability, which are scarce in Libya today.

Just a couple of days after his troops arrived in southern Libya, they killed Abu Talha, a leading Libyan jihadist with a record of fighting in both Libya and Syria.

As of today Haftar does not appear to be genuinely interested in the political process but this could change at any time. If the legal hurdles are removed and elections are held in the spring, as proposed, it would be the last chance for him to put on a civilian suit and aim for the presidency as a civilian.

This would be a gamble, not least because he would have to relinquish his military role as well as his US citizenship first. Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, though, is a man who is used to taking risks.

***

Mustafa Fetouri is a Libyan academic and freelance journalist. He is a recipient of the EU’s Freedom of the Press prize.

__________