By Agathe Duparc, Montse Ferrer & Antoine Harari

In Libya, a country that has been torn apart and bled dry since the fall of Gaddafi, international criminal networks with connections to Europe and Switzerland make big profits through fuel smuggling.

In Libya, a country that has been torn apart and bled dry since the fall of Gaddafi, international criminal networks with connections to Europe and Switzerland make big profits through fuel smuggling.

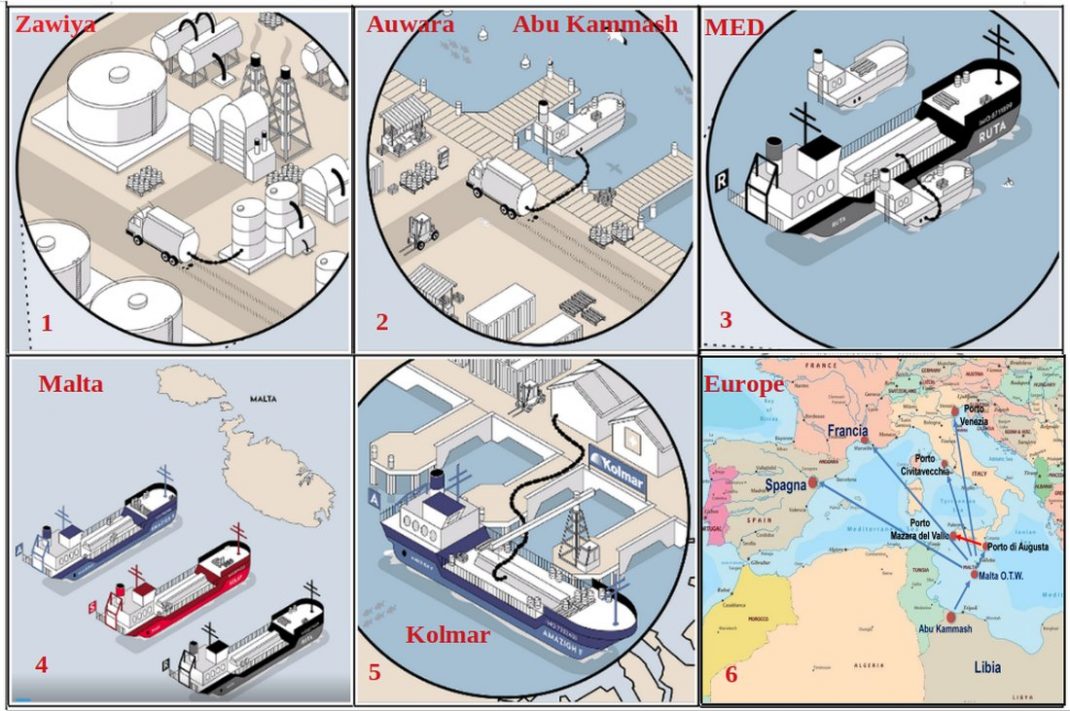

Public Eye and TRIAL International uncovered business transactions in 2014 and 2015 between the Swiss trader Kolmar Group AG and a smuggling network whose main players are now facing trial in Sicily. This is the story of a long-running investigation in Switzerland, Malta and Sicily.

PART FOUR

MALTA: A DUBIOUS DESTINATION

The profession has a habit of staying abreast of even the smallest rumours. By the summer of 2013 onwards, it was known that Malta had become one of the main bases for smuggled fuel from Libya.

In July 2013, the daily newspaper Malta Today revealed that one ship, the MV Santa Maria – which is not connected to the Ben Khalifa network – was requisitioned as part of a Maltese investigation, which led to arrests.

Gordon Debono was cited as the owner of another tanker which was also implicated. The investigation, about which very little information has been made available, seems to have gone nowhere .

A year later, on 18 June 2014, then prime minister of Libya Abdullah al-Thinni met the Maltese ambassador in Tripoli 19 to complain about the fact that large quantities of smuggled fuel were being diverted to the island.

‘This phenomenon is a threat to Libya and affects national security’ he added, calling on his interlocutor to act swiftly. The information was picked up by numerous media outlets, including Reuters 20 . One month earlier, Kolmar had started to receive shipments of fuel from the Ben Khalifa network.

A CLEAR RED FLAG

Other elements should have also dissuaded the Zug-based company. During the Dirty Oil operation, the Guardia di Finanza discovered that the Ben Khalifa network was selling products at prices significantly below the market rate, which is one of the first warning signs in the trading sector.

‘In our industry, any significant discount is automatically a red flag. A low price always means a high risk’, says a former trader. ‘Libya was in flames. It was the time when Libyan refineries were barely functioning or were damaged. The country was importing petroleum products – not the other way around – so purchasing fuel from Libya should have been a clear red flag’, stated a banker specialised in trading.

‘I struggle to imagine that a bank would be able to fund that kind of transaction, especially when it comes to fuel from Libya’ we were told by the former employee of a trading company who worked in the Mediterranean petroleum products market.

What about the bank that approved the transfer of over $11 million from Kolmar to Oceano Blu Trading Ltd? Even though the documents we have do not allow us to identify this institution, two sources informed us that the Zug-based company had – and allegedly still has – accounts at Credit Agricole Indosuez in Geneva, where it was given a credit line of CHF 100 million in recent years.

When contacted, Credit Agricole Indosuez (Switzerland) SA declined to confirm or deny its relationship with Kolmar, citing professional secrecy. The bank indicated that all of its financing activities ‘are carried out in strict compliance with the laws and regulations of the countries where it operates’.

It explained that it relies on a robust compliance framework, which enables it to fulfil all obligations related to combatting the funding of illicit activities.

The BNF Bank plc (formerly the Banif Bank [Malta]), which held Oceano Blu Trading Ltd’s accounts, responded to us stating that ‘due to confidentiality obligations, BNF Bank plc is not in a position to reply’.

RADIO SILENCE

Despite numerous requests for comment, Kolmar did not answer our questions. Darren and Gordon Debono and Fahmi Ben Khalifa, all three of whom we contacted through their respective lawyer, also did not respond to our requests.

For their part, the Maltese customs officers refused to comment, stating that there is an ongoing case. They did however highlight that whenever the Customs Department has a suspicion of any illicit activity and/or false documents being presented, the case is always referred to the police or other relevant competent authority.

Epilogue for the smugglers

From 2015 onwards, the other shoe begins to drop. Outside Malta, several lights turned yellow. In a UN panel report published in February 2015 21 , UN experts invited the Security Council to address the issue of fuel smuggling, as it was deemed ‘of great importance to the resolution of the conflict’.

Six months earlier, in August 2014, the Libyan authorities had provided the UN with information on an illicit shipment: 2,845,380 tonnes of gasoil loaded along the Libyan coast following a ship-to-ship transfer operation.

The UN experts described it as a ‘new phenomenon, even a trend’. The ship in question was the Ruta, one of Gordon Debono’s tankers. From the end of May to mid-June 2014, the ship offloaded Libyan gasoil at the the Ras Hanzir dolphin five times, where Kolmar was renting all of its gasoil tanks.

In autumn of 2015, Ann Marlowe, an American journalist specialized on Libya, published an exclusive investigation on the smuggler Fahmi Ben Khalifa in the Asia Times.

The article named some of his Maltese companies and the Amazigh F tanker. Despite this, Ben Khalifa, who enjoyed strong support, was still in the game.

On 23 November 2015 he obtained a letter from Ali al-Gatrani, chair of the Economic and Trade Committee of the House of Representatives (Libya’s recognized parliament at the time).

Al-Gatrani, who is close to General Haftar, testified that Tiuboda Oil and Gas Services – the new name of the Tiuboda Oil Refining Company – was registered with the relevant authorities in September 2012. Fahmi Ben Khalifa continued his activities for a few more months.

But in the summer of 2016 everything went pear shaped. Ben Khalifa’s protector, Ali al-Gatrani, made a full U-turn. In a letter to the Maltese government, he explained that subsidised Libyan petroleum products could not be exported by companies licenced for ‘oil services’ – a thinly veiled reference to the activities of Tiuboda Oil and Gas Services.

Three months later, the Tripoli NOC drove the point home by recalling that it had always been the sole entity authorised by law to import or export crude oil and its derivatives. The party was over.

After years of acquiescence, the Maltese customs authorities had finally decided to put an end to the import of Libyan gasoil into Malta, ‘forcing Darren Debono to transfer his business to Sicily where he was later caught by the Italian authorities’, explains one source. Kolmar left the small island at the beginning of 2016.

Our conclusions

The smuggling of natural resources fuels wars around the world; Libya is no exception. Companies involved in mining and extracting, shipping and commodity trading play an essential role in creating a profitable market for such conflict resources. But taking part in this supply chain can amount to a war crime.

If a company knowingly purchases a commodity that was stolen from a country at war, that company could be guilty of pillaging, a war crime under the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute (Article 8 (2)(e)(v)) and Swiss criminal law (Article 264g (c) of the Swiss criminal code).

WAS KOLMAR COMPLICIT IN PILLAGING?

Public Eye and TRIAL International’s investigation shows that the (legitimate) NOC did not authorise the export of any fuel from the Zawiyah refinery, lest of all to the Ben Khalifa network.

Rather, it was the Shuhada al Nasr Brigade, an armed group accused by the UN of exploiting and smuggling migrants, which allowed such fuel to be smuggled for its financial gain.

The Italian investigators uncovered the network of front companies established by Ben Khalifa and his associates to smuggle Libyan fuel into Europe via Malta and Italy.

All of that coupled with the bank statement showing that Kolmar paid over $11 million to Maxcom Bunker in just over a month, most likely in exchange for the offloading of fuel into Kolmar’s onshore storage units in Malta, which we were able to trace in our investigation.

These findings show that the fuel was (1) stolen from a country at war and (2) was received by Kolmar despite many red flags. Given these facts, it is possible that Kolmar committed (or aided and abetted) the international war crime of pillage.

BINDING RULES FOR TRADERS

Beyond the question of Kolmar’s criminal liability, this set of events provides a striking example of Swiss traders’ habit of profiting from highly volatile situations.

While civil war was raging in Libya and armed groups were fighting for control of the oil sector, the Zug-based company chose to do business with a tiny and obscure Maltese company with no experience in the oil business – even though the trading sector was aware of both the smuggling of Libyan fuel and the role played by Malta in relation to smuggling activities.

The Kolmar case also demonstrates that deals between well stablished trading companies and criminal networks take place.

BANKING SUPERVISION: A SPURIOUS ARGUMENT

For their part, the banks involved apparently did not conduct sufficient due diligence. This case thus further demonstrates the extent to which it is unrealistic and irresponsible to rely on the banking establishment to exercise ‘indirect supervision’ over traders, as the Federal Council does.

This is all the more so given that in the trading sector illegally sourced commodities can be ‘laundered’, as in the present case. It is therefore vital to impose heighted due diligence obligations on traders, in particular with regard to their business partners.

By proposing the establishment of a dedicated supervisory authority for the commodities sector, ROHMA, Public Eye has exhibited how such an authority could lay down clear rules and sanction companies that fail to comply with them.

A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY TO TAKE ACTION

A reasonable due diligence requirement with regard to human rights, as envisioned by the Responsible Business Initiative (and to a lesser extent by the counter-proposal put forward by the National Council), is crucial to put an end to these kinds of practices.

Companies would be required to assess the risks posed by their activities abroad and take measures to mitigate these risks.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas details such a procedure. In their initial 2010 version, the guiding principles focused solely on certain conflict minerals.

Five years later, the OECD Investment Committee decided to expand its guidance to all minerals, including petroleum.

If such non-binding provisions (‘soft law’) were transposed into Swiss national law, leaders would no longer be able to turn a blind eye, and would be obliged to prevent their businesses from contributing to serious human rights violations, such as those committed in the context of the civil war in Libya.

***

Agathe Duparc is a journalist for Le Monde.

Montse Ferrer is a Senior Legal Advisor and Investigator of the International Investigation and Litigation (IIL) program of TRIAL International.

Antoine Harari – Swiss freelance investigative journalist based between Geneva and Palermo.

___________

PUBLIC EYE For around fifty years, the Swiss NGO Public Eye has offered a critical analysis of the impact that Switzerland, and its companies, has on poorer countries. Through research, advocacy and campaigning, Public Ey world. With a strong support of some 25,000 members, Public Eye focuses on global justice.

PUBLIC EYE For around fifty years, the Swiss NGO Public Eye has offered a critical analysis of the impact that Switzerland, and its companies, has on poorer countries. Through research, advocacy and campaigning, Public Ey world. With a strong support of some 25,000 members, Public Eye focuses on global justice.

TRIAL INTERNATIONAL is a non-governmental organization fighting impunity for international crimes and supporting victims in their quest for justice. TRIAL International takes an innovative approach to the law, paving the way to justice for survivors of unspeakable sufferings. The organization provides legal assistance, litigates cases, develops local capacity and pushes the human rights agenda forward.

TRIAL INTERNATIONAL is a non-governmental organization fighting impunity for international crimes and supporting victims in their quest for justice. TRIAL International takes an innovative approach to the law, paving the way to justice for survivors of unspeakable sufferings. The organization provides legal assistance, litigates cases, develops local capacity and pushes the human rights agenda forward.